1.INTRODUCTION

There are a number of models of the cognitive processes underlying Internet navigation. Generally, these models assume that users are sensitive to some form of estimate of the likelihood that a link item will lead to some target information. However, the models differ in, for example, which link items are considered, and in the selection strategy that makes use of these estimates.

Miller [5] has classified models into those that assess links from either a 'threshold' or a 'comparison' approach. From the threshold perspective, a link is selected if it is above an established threshold. Otherwise, users proceed to the next link for assessment (e.g.[5]). From the comparison perspective, a user may first assess several links and then select the link with the highest relevance (e.g. [6][2]).

In this paper, we consider whether these strategies of user search are predictively useful when applied to first-click behavior. First-click behavior refers to what happens when a user (i) poses a query to a search engine to fulfil some information need, (ii) evaluates the result-list returned to that query and (iii) then chooses one of these results as a link to follow. We focus on first-click behavior as this presents us with a clean scenario for examining these factors in a search environment (e.g., repeated query refinement in a progressive search would be a lot more complex).

2.METHOD

Thirty participants were asked to answer 16 Computer Science questions (e.g. "Who invented Java?") by running as many queries as they liked on a simulated Google environment. The result set returned for a particular query came in one of two forms: (a) a normal presentation of Google's first page (top 10) results (b) a reversed presentation of Google's first page (top 10) results (see [3] for more details). From a modeling perspective the comparison approach obviously predicts no change in the results selected across both conditions - these models predict that users should hunt down the list to highly relevant results irrespective of their position in the list. Conversely, the threshold approach predicts the selection of quite different results across both conditions depend on what threshold is chosen. Bloodhound scent scores [2] were calculated as a means of modeling result relevance estimates. The search results were also manually ranked by a group of 14 raters to test the aptness of these scores.

3.RESULTS

The average user ranking for queries was found to correlate highly with the average search engine rank (r2=0.9124 t=9.13; df=8; p<.0001), demonstrating that the search-engine's relevance metrics closely parallel people's subjective estimates of relevance. The average user evaluation rank was also found to correlate highly with the average bloodhound score (r2=0.6665; t=-4 ; df=8; p<.001; figure 3). Obviously, then this automated method can be considered a viable means for modeling some aspects of people's assessments of the relevance of items.

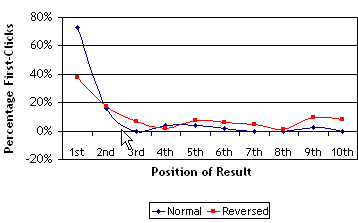

As Keane, O'Brien & Smyth [3] have shown behavior in the normal and reversed conditions of the experiment are not identical. Items with the highest-relevance ranks (i.e., items from the top of the normal Google result list) are chosen 70% of the time in the normal condition, but this rate drops to 10% in the reversed condition. In contrast, the 9th and 10th relevance-ranked items are chosen more often (13% and 41%, respectively) in the reversed condition than in the normal one (2% and 2%, respectively). Intermediately ranked items are much the same across both conditions.

Figure 1. First-Clicks across the normal and reversed conditions of the experiment (from [3])

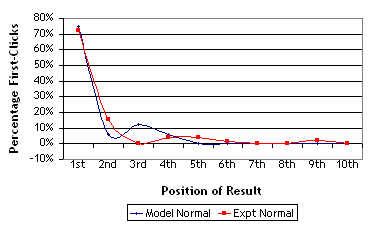

Figure 2. Comparison of predicted first-clicks by the threshold model and first-clicks in the normal condition of the experiment.

As the results across the two conditions were quite different the comparison approach to modeling the results fares less well than the threshold approach The comparison approach correctly predicts 25% of results in the normal condition, and 9% in the reversed condition. The threshold approach, on the other hand, proved reasonably successful (see Figure 2). Using a very simplified approach to threshold modeling whereby at each decision point (search-engine result) the model was faced with a binary decision to either pursue that result (Bloodhound score>0.1) or proceed to the next (Bloodhound score<0.1) the model correctly predicted over 61% of results in the normal condition. This is quite impressive considering the model's simplicity and that the base line chance level is 10% (1 in 10).

Recently Klockner et al. [4] analyzed eye movements over a Google webpage. They found that 65% of users applied a strategy in which they examined the search results list in turn, deciding immediately whether to click or not. Fifteen percent adopted a strategy in which they looked at all of the results in the list, and then clicked on the most promising results. The remaining 20% showed a mixed strategy and only sometimes looked ahead at the next few results. The threshold model obviously only models those that tend to examine and click on results sequentially.

This threshold model does not prove quite as successful at modeling the reversed condition (34%), though it still proved significantly better than its comparison counterpart (9%). The "reversed" condition's re-ordering of the results effectively changes the perceived quality of the highly-ranked results. From the results it is clear that users react to this degraded ranking and visit lower ranked links more frequently. It may be the case that users adapt their search strategies to different search situations and that when a list contains many low-relevant items they tend to perform a more exhaustive search than when a list contains many high-relevant items [1]. Thus, whilst this simplified threshold model does provide a reasonable approximation to human behavior, it does not do a good job at taking into account strategy changes that emerge from different relevance topologies in a result list.

Characterizing and modeling the dynamics of internet search has significant scientific and commercial value, and the ability to accurately predict user surfing patterns could lead to a number of improvements in web search. A comprehensive model of user-search-engine interaction, for example, could enable both users and designers to understand and address recent concerns surrounding the search-engines power to route traffic. The work presented in this paper needs to form part of a larger effort to achieve this research goal.

4.ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the Science Foundation Ireland under grant No. 03/IN.3/I361 to the second and third authors. Thanks are also due to Karen Church for access to experimental data.