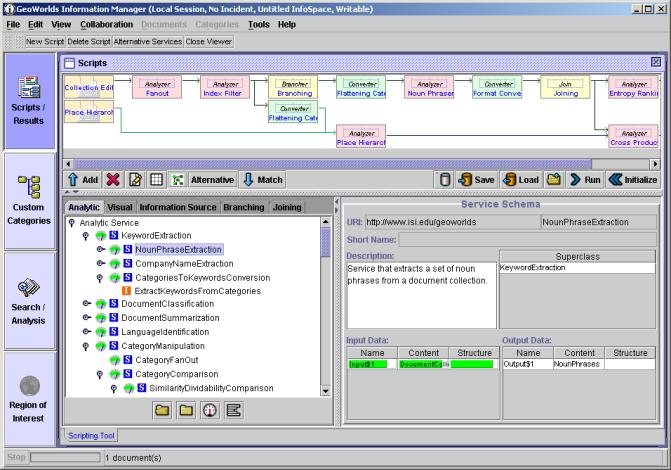

Figure 1. GeoTopics: An example of dynamic Web content processing application

Dynamic Web content provides us with time-sensitive and continuously changing data. To glean up-to-date information, users need to regularly browse, collect and analyze this Web content. Without proper tool support this information management task is tedious, time-consuming and error prone, especially when the quantity of the dynamic Web content is large, when many information management services are needed to analyze it, and when underlying services/network are not completely reliable. This paper describes a multi-level, lifecycle (design-time and run-time) coordination mechanism that enables rapid, efficient development and execution of information management applications that are especially useful for processing dynamic Web content. Such a coordination mechanism brings dynamism to coordinating independent, distributed information management services. Dynamic parallelism spawns/merges multiple execution service branches based on available data, and dynamic run-time reconfiguration coordinates service execution to overcome faulty services and bottlenecks. These features enable information management applications to be more efficient in handling content and format changes in Web resources, and enable the applications to be evolved and adapted to process dynamic Web content.

The Web is a nearly unlimited source of information. Recently, dynamic Web content that provides time-sensitive and continuously changing data has gained prominence. Examples of such time-sensitive data that people commonly access include news stories and stock information. During the September 11th terror attacks on the United States, the Web was one of the important information sources for many people to follow the dynamically changing information about the ongoing incident. The information sources they accessed on the day were dynamic Web sites, mostly news sites.

The coverage of individual Web sites that provide such dynamic content is often incomplete, since individually they are limited by time and resource constraints. To obtain a complete picture about time-sensitive or wide-range topics, people tend to access multiple Web sites. For example, during the terror attacks, since it was such a time-critical situation, no single news site could provide complete information to understand what was happening. People needed to browse different news sites to access different coverage and different opinions, then compile and assemble the information together to understand the full situation. In addition, to understand different reactions from different parts of the world, news sources from various countries needed to be accessed.

When visiting these multiple web sites to gather data, people often repeatedly perform the same sequence of retrieval and analysis steps. For example, to get the latest data about the terror attacks, people needed to repeatedly visit that site, retrieve the news articles, and read the articles. However, they exhibit dynamic behavior, making use of coordination strategies to help speed up their analysis process. If a Web site is unresponsive due to congestion, people tend to switch to another Web site and come back later. People exhibit other forms of dynamism as well. For example, they will select a different set of information sources based on their topic area and geographic region of interest, and they will mentally filter and analyze the news articles based on the articles' content, structure and format.

Any information management tool that supports this process of gleaning information for dynamic Web content should help alleviate the tedious and repetitive aspects, but should be flexible enough to allow users to incorporate the dynamic aspects of information analysis. This paper describes a dynamic service coordination mechanism that brings dynamism in information management systems for processing dynamic Web content. This coordination mechanism allows users to incrementally develop information management applications on different abstraction levels through the design/runtime lifecycle, which is essential for processing dynamic Web contents efficiently and correctly. This mechanism has been adapted by USC ISI's GeoWorlds system [5][6], and has been proven that it is practically effective on developing information management applications for processing dynamic Web content.

The characteristics of the class of information management problems addressed in this paper are:

The next section describes a sample information management application that requires dynamic service coordination to process dynamic Web content. Requirements to support dynamism in information management systems are also discussed in this section. Section 3 explains the multi-level, lifecycle coordination mechanism, which is the enabler for supporting efficient service coordination to process dynamic Web content. The active document collection template and dynamic parallelism are proposed as the main technique to realize the dynamic service coordination mechanism. Section 4 describes the run-time aspects of the dynamic coordination. Service proxies are explained as the entities to provide run-time dynamic coordination between service instances. The service proxies can perform dynamic parallelism specified in the application design, and enable run-time reconfiguration of the application. Related work is discussed in Section 5 followed by a conclusion (Section 6).

Although the Web itself was developed to support information management [3], as the size and density of the Web increases, users are having a more difficult time in locating, retrieving and organizing the information they need. Many users have resorted to using front-end information management systems, which access the Web as an information source and provide various information management tools. One such system is USC ISI's component-based GeoWorlds system, which handles both geographic and Web-based information. GeoWorlds combines Geographic Information Systems software with tools for finding, filtering, sorting, characterizing, and analyzing collections of documents accessed via the Web. GeoWorlds is currently in experimental use by the Crisis Operations Planning Team at the US Pacific Command (PACOM), and by the Virtual Information Center, also at US Pacific Command. Example uses at PACOM include: (1) mapping terrorist bombings in the Philippines; (2) locating patterns of recurring natural and technological disasters in China and India; and (3) investigating drug trafficking and piracy in various locales.

Figure 1. GeoTopics: An example of dynamic Web content processing application

As a test application for our dynamic coordination mechanism we have extended GeoWorlds to build USC ISI's GeoTopics1, an information management application that daily examines news reportage from the websites of a growing number of large, elite English-language news operations2. Its contribution is to help identify the "hot topics," and the most frequently referenced places, found that day in this very large collection of reports. The goal is to help users look at what's going on worldwide in either of two ways: what places are relevant to a topic, or what topics are hot in a place. GeoTopics also ranks topics and places by the number of references found to them that day. It automatically compares these to the previous days' results, flags new topics that emerged that day, and tells users whether ongoing topics seem to be getting more or less attention than the day before. For each days' topics and places, clicking on them gets users both the full set of reports under that heading and a breakdown of those reports (i.e., reports on each topic are broken down by places referenced, and reports on places are broken down by topics referenced). Figure 1 illustrates these major information management steps to generate daily GeoTopics results.

In principle, the underlying GeoWorlds system could be used to perform this news analysis task without the dynamic coordination mechanism. GeoWorlds' analysis services and visual editing facilities provide enough functionality that they could be chained together to generate similar results. However this generation process would be very labor-intensive. Currently with the enhancements it takes about 20 minutes to perform the daily updates for GeoTopics. Without the enhancements, it would take several hours.

Each of the information management steps depicted in Figure 1 is performed by a separate service component from the GeoWorlds system. The coordination between these information management services forms the GeoTopics application. That coordinated set of services can be reused for different set of information sources, and can be repeated for recurring analyses of the same set of information sources.

Although the high-level processing steps are the same (extracting articles, filtering and classifying them, and generating the HTML report), the selection and coordination of the information management services need to be flexible and reconfigurable to handle dynamic situations. For example, most of the 10 news sites, which are used for the current GeoTopics, have sidebars and footers in their articles, which cause false-matching problems (e.g., 'NASDAQ' was ranked high because it is appeared on the side bars in many of the news articles). The coordination mechanism allows an additional filter to be added to filter out the sidebars and footers, and to return only the pure article text. Also, when biased rankings are detected (e.g., 'Los Angeles' was ranked high because there were many LA Times articles that are about the city), a category weighting service can be added to give more weight value to the categories extracted from multiple news sources. Also, the coordination mechanism allows for alternative ranking services to be substituted, for example, a ranking service that weights values as well as the article counts.

The above reconfiguration occurs during the design phase of the application lifecycle, but dynamic reconfiguration during run-time is also needed. For example, when a Web-based document filtering service becomes a bottleneck the application should be able to dynamically bypass the filtering service or replace it with an alternative filtering service running on a less loaded server. This type of run-time reconfiguration is especially needed for the GeoTopics application because it requires processing of large number of articles,3 which takes long time. Also, it will be expensive to restart the entire GeoTopics application whenever bottleneck components are detected.

The dynamic service coordination tasks during the development time and run-time should be done without modifying the underlying information management system. It is also desirable for the end-users to do the application composition and reconfiguration tasks at the level where they can understand and manage instead of bogging down to the technical details. In addition, the reconfiguration process should not alter the original context of the information management task.

The requirements to support dynamic service coordination mechanism for processing dynamic Web content can be summarized as follows:

The next two sections explain our approach to implementing a dynamic service coordination mechanism that satisfies the above requirements.

Gelernter and Carriero define the coordination model as "the glue that binds separate activities into an ensemble," which is embodied by the operations to create the activities and to support communication among them [7]. To provide the mechanism to connect multiple services to perform complex information management tasks, and to make the information management application reusable and reconfigurable, we propose a multi-level, lifecycle service coordination model. This model makes it possible to compose and reconfigure an information management application on application and proxy levels, and at design- and run-times.

Figure 2. Multi-level, lifecycle service coordination

Figure 2 illustrates this model. The application-level provides the design-time coordination by allowing users to compose an information management application by sequencing high-level functionality they need. Using this mechanism, implementation details in selecting and connecting services can be hidden from the end-users during the application development. The composed application can be dynamically instantiated based on system environment, and then executed. During instantiation, the system suggests only the service instances that provide the required functionality as well as semantically and syntactically interoperable with the existing services in the application.

When a composed information management application is instantiated, a set of proxies is created. A proxy is the run-time entity that interacts with a service instance. It performs run-time coordination between other service proxies, such as data bindings between inputs and outputs of the services, data-driven activation of services, and synchronization between services. Proxies allow the application to access service instances in a transparent and unified way, and make the application design independent from the invocation and communication syntax.

Each proxy interacts with its corresponding service instance using a predefined service interface. To interact with an analysis service, the proxy accesses GeoWorlds' job pool interface, which is the interface to our asynchronous, distributed service invocation architecture [11]. Using the job pool, proxies can transparently invoke and monitor distributed service instances. To interact with other types of services, proxies use a language specific interface for each service type (see Section 3.3 for the service type definitions). During run-time, the application can be reconfigured to improve result quality or to replace faulty services with alternates.

Web information management is a cascading process applied to a collection of documents. An initial document collection retrieved from the Web is passed through a sequence of filters to be refined, and is then processed by various analysis services to be classified and reorganized. Therefore, the coordination between services needs to be data-driven and data-flow-based. Outputs of a service become inputs of subsequent services, with each service activated when its input requirements are satisfied.

Active document collection templates provide the mechanism to represent data-centric coordination of services for information management applications [8]. In an active document collection template, the actions of transforming a document collection from one semantics to another are described. Document collection semantics is represented in dual ontologies (cj, sj) that characterize the content (cj) and structure (sj) of the collection, and action semantics (fj, ij, oj) is represented by describing its functional ontology (fj) and I/O data semantics (ij and oj). An information management application can be composed by describing a chain of active relations between documents from the initial collections to the target collections.

Figure 3. Active document collection template for the GeoTopics application

Figure 3 shows a part of the active document collection template for the GeoTopics application. The initial document collection D1 is a collection of news media home pages, which is a set (the structure semantics s1) of HTML documents (the content semantics c1). From each of the documents in the collection, the document extraction service F1 collects today's articles. F1 accepts a set of HTML documents (the input semantics i1), performs the document collection fan-out function4 (the functional ontology f1), and generates output document collection in which documents are classified by news sources (the output semantics o1). Then, the output of F1 passes through a filter that removes static documents such as weather and stock information pages. For each sub-collection (articles from a news source) in the filtered collection D3, the noun-phrase extraction service F4 is performed. The service reorganizes its input collection such that documents are classified by the noun-phrases referenced in their content. The branching service F3 dynamically creates multiple noun-phrase extraction service branches based on the number of sub-collections in its input collection D3. Then, the branches are joined by the joining service F5, which merges results from each noun-phrase extraction service (see next subsection for more details on dynamic branching and joining mechanisms). The merged result D6 is further processed by subsequent services such as sorting and ranking services.

Another main branch described in Figure 3 is the sequence of services (F7 and F8) for classifying the filtered documents D3 based on the place names cited in their content. The place name generation service F7 imports place names in a selected region on a map, and creates a set of place names with geo-location information (e.g., Latitude-Longitude coordinates) D7, which will be used by the document classification service F8. D3 and D7 are grouped together as a data set to describe active relation between F8's output collection D8. In the same way, D6 and D8 are grouped together to be passed to the cross-product service F9, which sub-divides the noun-phrase-based document classification by the place names.

The active document collection does not specify particular service instances to use nor detail data bindings between them. It only describes the functional requirements to transform the initial document collection to the target semantics. This template can be dynamically instantiated by allocating different set of service instances and by combining them with using different bindings based on availability and condition of the Web information sources and services. This makes the application development process reusable and flexible.

Since active document collection templates support the data-driven control mechanism, the control-flow does not need to be explicitly specified within the application specification. During run-time, a service is activated when its input requirements are met. For example, the place-named-based classification service F8 is activated when its predecessor services (F2 and F7) generate the filtered document collection and a set of place names (D3 and D7), which are inputs to F8. This data-driven service control mechanism simplifies the coordination design and execution steps, and maximize the concurrency among services (see Section 4 for more details about run-time coordination mechanism).

Figure 4. Service Composition Tool

USC ISI's TBASSCO (Template-based Assurance of Semantic Interoperability in Software Composition) project5 develops software gauges to measure semantic interoperability and compatibility between software components, which help application developers build active document collection templates efficiently and correctly [12]. Also, the project develops a GUI tool (Figure 4) by which users can easily compose, instantiate and execute active document collection templates. The upper part of the service composition tool currently shows the data-flow diagram of the GeoTopics application illustrated at Figure 3. The lower-left part of the tool displays the hierarchies of interoperable services for an existing service, and the lower-right part displays the detail description (functionality and I/O data semantics) about the selected service.

By composing an active document collection template, an information management application can be described as data-flows among information management services. The next subsection describes how concurrent data-flows can be specified in an active document collection template to represent dynamic parallelism in processing dynamic Web documents.

In a large-scale information management system, which processes a large quantity of data, it is critical to support parallelism in executing services to improve performance. To efficiently process dynamic Web content, the number of service branches that execute in parallel needs to be dynamic. For example, in the GeoTopics application illustrated at Figure 3, the service branch D4-> F4->D5 that extracts noun-phrases from a sub-collection needs to be dynamically forked based on the number of sub-collections in the input collection D3.

Special service types, branching and joining services are supported to describe dynamic parallelism in active document collection templates. This allows users to represent dynamic parallelism without explicitly describing multiple data flows or a loop for forking multiple threads of services in an application. Branching services provide the actions that subdivide their inputs and generate a sequence of multiple data blocks to activate subsequent services multiple times. Joining services join branches that are created by a branching service by merging results from their immediate predecessor services.

In the context of sequential computing, the branching and joining are similar to the map function in LISP. They both have the effect of performing a for-each-element-in-list-do loop without actually using loops, which are more difficult to analyze. In the context of parallel computing, the branching and joining can be interpreted as forking out separate execution threads/processes then merging them back together again.

For example, at Figure 3, the branching service F3 has been added to dynamically create multiple branches of the noun-phrase extraction service. This branching service generates multiple data blocks by sub-dividing its input document collections based on the news sources. F5 is the joining service that joins the branches created by F3. It collects results from the noun-phrase extraction services and merges them by unifying the noun-phrase-based document classifications (i.e., if more than one noun-phrase services return the same noun-phrase, the joining service unifies the documents classified under the noun-phrase). The dotted line specifies the document collections and services on dynamically generating branches.

Therefore, although a branching service describes active relation between two document collection types in an application design, it implicitly represents n sub-collection relations between its input document collection and n output sub-collections. Similarly, a joining service implicitly represents n merging relations between its n input collections and the output document collection.

Figure 5. Branch types: (a) Open branch; (b) Partially open branch; (c) Nested branches

Open branches can be represented either by not including the corresponding joining service or bypassing it. Figure 5 (a) and (b) illustrate examples of these open branches based on the GeoTopics application. The service branch shown at Figure 5 (a) does not include the joining service that joins the branches created by F3. Therefore, the service F10, which is the visualization service that displays a histogram of the noun-phrases extracted from a document collection, will be executed for each noun-phrase extraction result (i.e., the system will display a noun-phrase histogram for each news source). At Figure 5 (b), the open branch for F10 is created by bypassing the joining service F5. By doing this, the action of displaying multiple histograms can be described along with the further analyses on the merged noun-phrase extraction result.

Nested branches also can be represented by using multiple pairs of branching and joining services. The nearest branching service is matched against a joining service. There can be more than one joining services that join braches created by a branching service. However, branches created by non-nested branching services cannot be overlapped, i.e., branches created by different branching services cannot be joined by a joining service.

Figure 5 (c) shows a part of an extension of the GeoTopics application, which performs worldwide topic analysis. A collection of worldwide news home pages D0 is provided as the input to the application. In the input collection, the home pages of major news media in each country are classified under the country names. A new branching service F0 has been added to the application to dynamically create multiple branches of processing news articles for each country. To join the branches created by F0, a joining service F11, which combines each country's noun-phrase list and generates a worldwide topic list, has been added. Addition of these new branching and joining services creates a nested branching structure in which the branching-joining pairs are (F0, F11) and (F3, F5). To generate a different type of merged noun-phrase list and perform further analyses on it, an additional joining service F12 has been added. This joining service joins the branches (that are created by F3) by intersecting the noun-phrase lists generated for the news sources in each country, and creating a list of common-topics for each country. By adding this, another branching-joining pair (F3, F12) is created. Therefore, both F5 and F12 are the joining services that join the branches created by F3.

Since branching and joining activities are represented as "services" in a template, they are also activated and managed in the similar way that is used for handling regular services during run-time. Section 4.2 will explain more details about run-time mechanism for supporting the dynamic branching and joining.

Representing dynamic parallelism by using branching and joining services brings us following benefits:

Different types of information management services have different characteristics and require different handling in each level and lifecycle of the coordination. Based on input/output requirements and functionality, the services are classified into different types: analysis, converter, visualization, input, information sourcing, branching and joining services.

Analysis services have both inputs and outputs, and provide actions that produce output document collections that have altered semantics of the input document collections. These services are normally heavyweight and may require specific run-time environment (e.g., specific operating system or high-performance computing environment). Also, multiple service instances may coexist in a network, and dynamically be selected (based on server load and other run-time conditions) and remotely accessed.

Reorganization, filtering, processing and manipulation services are the major analysis services used in the current GeoWorlds system. Reorganization services reorganize an input document collection by classifying and/or sorting documents and categories (e.g., a service that classifies documents based on company names referenced, and a sorting service that reorder the categories based on the number of documents classified). Filtering services produce a subset of an input document collection by excluding certain documents or categories based on criteria specified in another input (e.g., a service that removes documents that are more than 7 days old). Processing services are the services that process the content of each document in an input collection, and add additional properties as the result (e.g., a document summarization service that generates a short summary of each document and add the summary property to the document). Manipulation services normally accept multiple document collections as inputs, and perform various manipulation actions such as comparison, merging, subtraction, and cross product (e.g., a service that analyzes similarity between two different sets of categories by comparing documents classified under the categories).

Converters also have both inputs and outputs. However, they are lightweight and local services that can be executed on the client side. Converters do not alter the content semantics of the input document collection and perform simple functions to generate different syntactic representation of the input collection (e.g., converting a hash table representation of a category structure to a vector representation).

Visualization services publish document collections into a visual form. Visualization services only have inputs, and the results are generated in the forms of GUIs (e.g., a histogram of noun-phrases extracted from a document collection) or data files (e.g., a HTML file that shows a category structure) that can be browsed by other tools. Visualization services are also provided as local services.

Input services are also local services that display GUIs and accept user inputs. The input data entered by the user are packaged and generated as outputs to other services. A search engine query tool is an example of the input service that provides a GUI to write a query string and to select various query options.

Information sourcing services are the services that retrieve documents from the information sources such as the Web, local files, and remote databases. These services normally require user inputs (e.g., URLs, file names and database queries) that can be provided by using input services. For example, an online yellow-page wrapper is an information sourcing service that accepts a query (a name of business type and the city to search) through a query input service, submit the query to a yellow-page site, and collects the search results. Information sourcing services can be either local or remote services.

As explained at Section 3.2, branching and joining services are for representing and performing dynamic parallelism in an application. Branching and joining services are local services that perform similar lightweight functions (subdividing or merging document collections) as converters.

Based on these service types, a set of standard service interfaces is defined. These service interfaces are language-specific6 and can be used to wrap heterogeneous service instances and make them accessible by the information management system. Also, behaviors of a proxy can be determined depending on these service types during the service instantiation time. The next section explains how run-time proxies are created and managed based on these service types.

An active document collection template does not specify exactly which service instances will provide the information management functions specified. To run the information management application, a local or remote service instance must be selected and allocated for each service component in the active document collection template. In addition, for each service component, we need a run-time entity that interacts with the allocated service instance and performs the dynamic parallelism specified in the template during run-time.

We use the proxy-based mechanism to provide these run-time features. Proxies are created during the application instantiation time, and establish connection with other proxies by making I/O data bindings. During run-time, each proxy activates and monitors the corresponding service instance, and performs synchronization between other service proxies. Proxies also perform dynamic branching and joining actions by exchanging run-time tokens. The application can be reconfigured during run-time by reallocating service instances and switching proxies. The next three subsections explain the mechanisms to instantiate, execute and reconfigure the information management applications.

An information management application design represented in an active document collection template can be dynamically instantiated by allocating local and remote service instances. During the instantiation time, the service composition tool (Figure 4) suggests users a set of semantically valid service instances for each service component in the template. This makes the instantiated application maintain the same context as the original design, and perform the same type of information management tasks.

The service instantiation process is a creation of a client-side proxy that

activates the service instance, monitors its execution, and processes the

results during run-time. Different types of proxies are created for different

types of services. Each proxy keeps the information and methods for

interacting with the service instance (e.g., location of the service instance

and the interface to access it). When a proxy is created, placeholders for I/O

data are also created. For example, at Figure 6,

1

and

1

and  2 are created to hold

input document collections for the service proxy of the service F1.

2 are created to hold

input document collections for the service proxy of the service F1.

1 and

1 and

2 will point to the

actual data objects when the input document collections are available during

run-time. Similarly,

2 will point to the

actual data objects when the input document collections are available during

run-time. Similarly,  3 and

3 and

4 are created to store

the result data generated by the service instance F1.

4 are created to store

the result data generated by the service instance F1.

Figure 6. Connections between proxies

When two adjacent services are instantiated, the instantiated proxies need

to be connected to each other. The connection between two proxies is

established by binding their I/O data, and creating precedence relations

between them. Since the active document collection template does not include

binding information between the services, this data binding is done

dynamically during the instantiation time by matching semantic requirements of

the I/O data. For example, at Figure 6, the first output data

3

of the first proxy has been bound to the input of the second proxy because

the input semantic requirement of the second service instance is matched to

the data semantics of

3

of the first proxy has been bound to the input of the second proxy because

the input semantic requirement of the second service instance is matched to

the data semantics of  3.

When the service composer detects a syntactic mismatch between

semantically matched I/O data, it automatically searches for appropriate data

converters and inserts them (by creating and inserting proxies to interact

with the converters) to resolve the mismatch between data representations.

When there are more than one possible bindings between adjacent service

proxies, the service composer asks the user to select one of the multiple

bindings. It also asks the user to choose one of the available converters when

multiple ones are found. [8]

describes the detailed mechanisms to represent and compare I/O data semantics

of information management services.

3.

When the service composer detects a syntactic mismatch between

semantically matched I/O data, it automatically searches for appropriate data

converters and inserts them (by creating and inserting proxies to interact

with the converters) to resolve the mismatch between data representations.

When there are more than one possible bindings between adjacent service

proxies, the service composer asks the user to select one of the multiple

bindings. It also asks the user to choose one of the available converters when

multiple ones are found. [8]

describes the detailed mechanisms to represent and compare I/O data semantics

of information management services.

Document collections that are bound to inputs or outputs of a service proxy

are grouped together as a data set during the instantiation time. For example,

at Figure 6, since  3 and

3 and

4 are the outputs of the

first proxy, they are grouped together as the data set t2.

Similarly, the data set t3 is created to include the input data

4 are the outputs of the

first proxy, they are grouped together as the data set t2.

Similarly, the data set t3 is created to include the input data

3

for the second proxy. These data sets form a data chain between the

service proxies (e.g., t2 and t3 are chained together).

Data chains are used to establish data-driven precedence relations between

proxies. Predecessors of a service proxy can be determined by finding the

service proxies which output data set is chained with the input data set of

the service proxy. For example, at Figure 6, the first proxy is the

predecessor of the second proxy because the output data set of the first proxy

is chained with the input data set of the second proxy through the document

collection

3

for the second proxy. These data sets form a data chain between the

service proxies (e.g., t2 and t3 are chained together).

Data chains are used to establish data-driven precedence relations between

proxies. Predecessors of a service proxy can be determined by finding the

service proxies which output data set is chained with the input data set of

the service proxy. For example, at Figure 6, the first proxy is the

predecessor of the second proxy because the output data set of the first proxy

is chained with the input data set of the second proxy through the document

collection  3.

When the precedence relation is determined between service proxies, the

predecessor and successor links are explicitly added between them, and these

links will be used to activate and synchronize the services during run-time.

3.

When the precedence relation is determined between service proxies, the

predecessor and successor links are explicitly added between them, and these

links will be used to activate and synchronize the services during run-time.

An instantiated application is also reusable. The application can be periodically rerun to collect latest document collections from the dynamic Web resources, and update the analysis results. Also, the same set of service instances and the same coordination plane can be applied to different information sources to perform the same type of the information management task.

A service proxy is activated when it receives activation signals from all the predecessors (input data producers). When a proxy is activated, it packs (marshals) the input data and sends them to the service instance by using the service interface. Then, the proxy monitors the status of the service and performs appropriate actions according to the status information received (e.g., writing status messages or handling errors). When the proxy receives result data from the service, it unpacks (de-marshals) the data, stores them to the output data placeholders, send activation signals to its successors, and finalizes its execution. Each activated proxy occupies a separate thread for its execution.

The input services, which do not accept input data, are directly activated by the service composer when an information management application is executed. Visualization services are usually the terminal services in an application, and they do not have successors to activate.

When a branching service proxy is activated, it calls its subdivision service instance, and disseminates the information about the branches that will be created to its successor proxies. The branch information includes an identifier (branch group token) of the group of branches and the number of braches to be created. When a joining service proxy receives the branch information, it keeps the information, and uses the information to determine the time when the branches must be joined. A branching service proxy may receive branch information from another branching service (an outer branching service proxy). In this case, it appends its own branch group token to the token received from the outer branching service. When the nearest joining service receives such a compound token, it takes out the last token component, and forwards the rest of the token to its successors. By doing this, the nested branching structure can be handled during run-time.

After the branch information is disseminated, the branching service activates its successor proxies for each subdivided data. For each invocation, it issues a branch token that identifies the branch created for the subdivided data. The branch token is composed of the branch group token and the branch number. When a joining service receives this branch token, it compares the branch group token with the one kept in it. If they are matched, the joining service increases its join counter. Otherwise, it forwards the token to successor service proxies. When the join counter of a joining service reaches to the number of branches in the branch group, it joins the branches for the group and sends the merged results to its successor proxies.

The virtue of this token-based parallelism control is that the same set of proxies can be reused for multiple parallel branches. This prevents creating too many service proxies and their execution threads, which may overwhelm the information management client. It also enables scalable parallelism support during run-time.

It would be an expensive job to rerun an entire information management application whenever a faulty service is detected during an execution. Especially, for a time-critical dynamic information management task, it will be unacceptable. Therefore, it is necessary to provide a run-time reconfiguration mechanism, by which services that failed can be switched to alternate instances without affecting other parts of the application.

There are three ways to detect faulty services: by spotting bottlenecks, by catching errors, and by monitoring the quality of intermediate results. For example, in GeoTopics, a remote document filtering service may become a bottleneck when the network gets slow or the server is overloaded. The filter may also generate many errors when its intermediate result files are damaged or the local file system gets full. The filtering results may be degraded when the formats of the dynamic Web content is changed to the formats that cannot be correctly handled by the filter.

Using the same mechanism of instantiating a service, a set of compatible service instances can be found when a faulty service is to be replaced. When the user selects a specific service instance, the current running proxy will be halted. Then, the input/output data sets, current execution status (the current indices to the input document collections), and intermediate results are retrieved from the halted proxy. Using the I/O data sets, the new proxy of the selected service instance will be connected to the neighboring proxies. When the new proxy invokes the service instance, it passes the execution status and intermediate results of the previous execution in addition to the original input data. Then, the service instance starts processing the input data from the point where the previous service instance was halted, and merging results to the intermediate results.

In current GeoWorlds system, run-time switching feature is only supported for analysis services. This is because the analysis services are usually heavy weight and can be remotely located, and these conditions are more likely to create faulty behaviors. However, not all the analysis services are currently run-time switchable. Only the stateless services that do not accumulate run-time status (other than indices to the input collection and intermediate results) are run-time switchable. Most of the filtering and processing services are run-time switchable.

The TBASSCO project is investigating efficient ways to detect faulty services during run-time. The project is developing probes and gauges to detect bottleneck conditions, monitor excessive exceptional conditions, and evaluate result quality. The project also develops the mechanism to switch services in high-degree of parallelism.7

When the GeoTopics application is instantiated and executed, it initially invokes input services that display GUIs (e.g., forms and editors) to acquire input data from the user. The input data required for GeoTopics includes a list of news sites, a set of keywords to classify articles, a set of place names8 to classify and map the articles, etc. The GUIs of the input services are displayed in the lower part of the service composition tool (Figure 4). Some of the input data can be saved with the application and reused for future analyses.

After acquiring all the required input data, the service coordination engine passes them to subsequent service proxies to activate the information sourcing and analysis services that are explained in Section 3.1. During run-time, the progress status of each service is displayed on the corresponding node in the data-flow diagram (the upper part of Figure 4). Bottleneck or erroneous services will be reported to the user by blinking the nodes or displaying error messages. The user can switch such faulty services to alternative ones during run-time as explained in the previous section. When the analysis services are successfully finished, visualization services are activated to present the results in certain formats (e.g., a histogram view of noun-phrases, a tree view of a document classification, a 3D bar chart that graphically compares two different categorizations). These viewers are displayed in the lower part of the service composition tool or in external windows if they are required.

The second portion of the GeoTopics application is then executed and allows the user to examine the visualized results and organize a customized collection by removing irrelevant items and merging similar document categories. Then, the refined result collection is sent to a HTML report generation service that creates a set of HTML documents to visualize the collection and publishes them to the GeoTopics Web site. During this result customization process, the user can also examine the noun-phrases newly discovered from today's articles, exclude noise and irrelevant ones, and merge the refined noun-phrase set with the current keyword collection. This populated keyword collection9 will be used for the next day's GeoTopics analyses.

Arbab classifies coordination mechanisms along two dimensions: data-oriented versus control-oriented, and endogenous versus exogenous [2]. Data-oriented coordination mechanisms focus on manipulating centralized, shared data, whereas the control-oriented coordination mechanisms focus on subsequent transformation of input data into new data. Endogenous coordination mechanisms require incorporating coordination elements within computational modules. In exogenous coordination mechanisms, coordination elements are separated from the computational modules.

The coordination mechanism presented at this paper is for processing dynamic Web content and generating analysis results that can be consumed by human users to easily comprehend the large quantity of Web content. It is not for manipulating and updating the Web information sources. Therefore, our coordination mechanism can be classified as a control-oriented coordination type. As an initial Web document collection is processed by the coordinated services, it is refined, reorganized and visualized. Run-time coordination between service proxies is done by using data-driven controls (data-driven activation and dynamic branching of service processes).

Our multi-level coordination mechanism clearly separates the coordination elements from the information management services. At the application level, information management services are regarded as black box components. An information management application is composed by creating an active document collection template, which is a high-level, data-centric information management plan that does not include any codes to interact with specific service instances. The service proxies interact with service instances during run-time by using standard interfaces. Therefore, our coordination mechanism can be classified as exogenous.

MANIFOLD [1] is a coordination mechanism for high-performance, parallel computing. It is also classified as control-oriented and exogenous. MANIFOLD provides a coordination language to describe connections among a set of independent, concurrent processes, and enables applications reuse existing algorithms and modules. The role of Manifold processes is similar to our service proxies. A Manifold process performs actions of activating/deactivating a computing process, and sets up connections between other manifold processes. However, MANIFOLD is a stream-based, stateful coordination mechanism, and run-time coordination between manifold processes is control-driven. Therefore, it is hard to support run-time reconfiguration in MANIFOLD.

IBM's Web Services Flow Language (WSFL) [9] is an XML-based language that is for coordinating individual Web services to compose high-level business processes. Communication ports (I/O message types) and operations of each Web service are described using Web Services Description Language (WSDL) [4], another XML-based language. By using WSFL, a sequence of Web service activities and the flow of data and control among them can be defined. Control links describe precedence relations and transition conditions among the activities, and data links specify mapping between I/O ports of the activities. Similar to our active document collection templates, WSFL allows users to compose a business process at the abstract-level by describing the sequence of required activities. The abstract level design (model) can be instantiated by binding the activities in the model with methods provided by service providers (service instances). However, WSFL does not include a representation mechanism to specify dynamic coordination behaviors.

Composition of a larger, higher-level software system by using a coordination language is also one of the major concerns for the CHAIMS (Compiling High-level Access Interfaces for Multi-site Software) project [10]. It focuses on providing a mechanism to compose and run software services that are composed of multiple megamodules. Megamodules are autonomous, heterogeneous, distributed, and normally computation and/or data intensive software components. These are similar to our information management services. CLAM (Composition Language for Autonomous Megamodules) is a service composition language by which domain experts can describe data and control flow between megamodules. CHAIMS supports late bindings of megamodules to a CLAM program, which enables dynamic selections of software components during compile-time. This feature is similar to our active document collection template composition and instantiation mechanism. However, CHAIMS provides only a name-based component selection mechanism. No explicit semantic description and processing mechanisms are supported. This assumes that the domain experts are very familiar with functionalities of megamodules and interoperability among megamodules, which is not necessarily the case. Furthermore, it means that CHAIMS cannot automatically identify alternate services in the event of bottlenecks or errors, as allowed in our approach.

This paper describes a dynamic coordination mechanism that facilitates the creation of information management applications for processing dynamic Web content. Its active document collection templates allow information management services to be linked together to process repetitive, but complex tasks. Dynamic instantiation and run-time reconfiguration enable these templates to be adapted and tailored to suit specific analysis tasks and execution environments. Dynamic parallelism facilitates the processing of large amounts of data from multiple sources.

This multi-level coordination mechanism supports both the design-time phase and run-time phase of the software lifecycle. It allows users to compose information management applications at a high-level, where they can concentrate on coordinating service activities for the target application. The application design can then be dynamically instantiated and executed by the system, based on run-time conditions and availability of the service instances and information sources. Service proxies bridge the gap between the high-level service descriptions defined in an application and the service instances, by providing the methods to activate and communicate with the service instances. When an application is instantiated, the proxies are created and connected with each other through data chains. The proxies can be reconfigured to interact with different service instances during run-time. This run-time reconfiguration feature allows the application perform more robust and efficient information management tasks on dynamic Web content.

Dynamic parallelism is represented by using explicit branching and joining services. During run-time, the concurrent service branches are created and joined dynamically based on the content and structure of Web document collections and intermediate results from other services. Context-sensitive parallelism can be achieved by selecting different types of branching and joining services.

Using our dynamic coordination mechanism, we were able to quickly develop GeoTopics, a Web-based information management application that collects and analyzes news articles from major English language newspapers. The initial GeoTopics application was created in less than two weeks, and the daily manual labor needed to perform the news analysis and to maintain the GeoTopics website takes less than 20 minutes. Without the dynamic coordination mechanism, GeoTopics would have taken months to implement, and maintenance of the site would take several hours daily.

Effort sponsored by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and Air Force Research Laboratory, Air Force Materiel Command, USAF, under agreements F30602-00-2-0610. The U.S. Government is authorized to reproduce and distribute reprints for Governmental purposes notwithstanding any copyright annotation thereon. The views and conclusions contained herein are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as necessarily representing the official policies or endorsements, either expressed or implied, of the DARPA, the Air Force Research Laboratory, or the U.S. Government.

We also would like to thank Juan Lopez, Baoshi Yan, and Robert MacGregor for their contribution to develop GeoTopics.