In this poster we illustrate some data about the African web. These data have been collected using UbiCrawler, a distributed Web crawler designed and developed by the authors.

The purpose of this poster is to present some structural information on the African Web, obtained by means of a distributed Web crawler [1]. Since classifying the nationality of a .com or .net site is a debatable process, we have been filtering sites by using suffixes of African Internet addresses. Therefore, with the term "African web" we mean the set of web sites whose address ends with the suffix of an African country.

The results we get suffer from the widespread use of .com and .net domains [2]. However, our choice has also some advantages. First of all, we divide URLs by country, and thus measure the degree of interconnection. Second, we believe that nationally based servers best reflect the status of awareness of web technology in Africa. Sites with other suffixes are often outsourced or externally hosted, and thus do not really reflect the degree of technology of the customer.

The already mentioned report [2] by Jensen, dated May 2001, puts into evidence some important characteristic of the African Internet. First of all, the Internet has grown rapidly in Africa, especially over the last 2-3 years, although it has been largely confined to major cities; recent estimates of the number of African Internet users give figures around 4 million in total, with about 1.5 million outside of South Africa. Another interesting issue is that of connectivity: it turns out that "Aside from local Internet links between South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland network and a link between Mauritius and Madagascar, there are no other regional backbones or links between neighbouring countries." [2]. Our results complement and give further evidence to some of the above observations. Whenever relevant, we give comparisons with companion data we have gathered for the .com and .it domains.

In this section we briefly discuss the tools used to perform the data collection and analysis.

Data Collection. We collected about 2,000,000 pages using UbiCrawler (formerly named Trovatore) [1], a distributed web crawler we developed to gather data about the web, starting from a seed of about 2,500 sites (chosen from popular directories and search engines sites). The downloading of the pages started on 9 February 2002 and required one day to be completed, due to the very high latency and low network bandwidth of the African internet [2].

Data Extraction and Manipulation. Data have been extracted using tools integrated with UbiCrawler; in particular, HTML parsing was performed using standard Java 1.4 API [11]. Hence, data was processed both with ad-hoc statistical tools and R [6], a sophisticated language for data analysis and plotting.

Language Recognition. We used text_cat, a tool for n-gram based text categorization [4].

The large majority of pages in the African domain does not have a document type (the DOCTYPE declaration is mandatory in SGML documents, and very important for validation). A report about the English web in 1997 [3] showed that 25% of the documents online had a DOCTYPE declaration. Most documents declaring a document type stating that they conform to HTML 4, but there are still pages using a HTML level of 3 or lower.

| DOCTYPE | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| HTML 4 | 150965 | 7.71% |

| HTML 3 | 81505 | 4.16% |

| HTML 2 | 40528 | 2.07% |

| HTML 1 | 693 | 0.03% |

| none | 1542191 | 78.81% |

| other | 139642 | 7.11% |

The distribution of headers in pages does not seem to differ significantly from data which are known for more general investigations on the Web. The only relevant difference is the almost complete absence of the p3p header, specifying the privacy policy, which ranks eleventh (13.68%) in the .com domain.

| Header | % |

|---|---|

| content-type | 99.88% |

| server | 99.71% |

| date | 99.16% |

| connection | 96.00% |

| content-length | 64.80% |

| last-modified | 43.70% |

| accept-ranges | 42.57% |

| etag | 41.05% |

| set-cookie | 34.00% |

| cache-control | 31.98% |

The majority of sites in the African domain use Microsoft® technology. The figures about IIS and Apache are almost exactly exchanged with respect to the trend of the world-wide web as reported by the NetCraft survey [4] (Apache 63.69%, IIS 26.97%); they are also different from the .it domain, where their figures are about the same (~45%).

| Server | % |

|---|---|

| Microsoft-IIS | 56.10% |

| Apache | 37.95% |

| Netscape-Enterprise | 1.50% |

| Lotus-Domino | 1.04% |

| Apache-AdvancedExtranetServer | 0.92% |

| WebSitePro | 0.30% |

| WebSTAR | 0.29% |

| Oracle | 0.21% |

| Netscape-FastTrack | 0.19% |

| IBM | 0.15% |

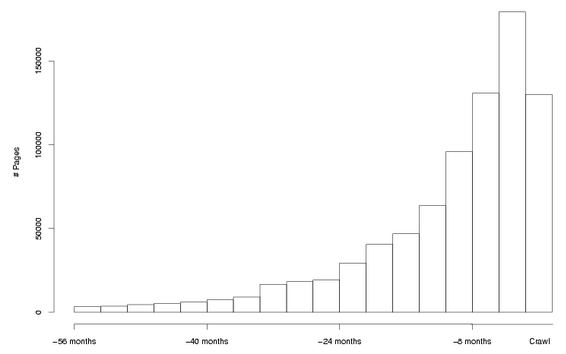

The distribution of last modification dates, as emerging from HTTP headers, is concentrated around the month preceding our visit of the African Web.

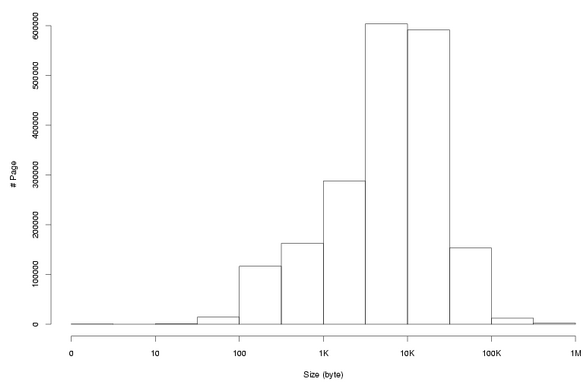

Figure 2 shows the histogram of page sizes (in logarithmic scale); the data obtained agree with those presented in other works analyzing local portions of the web (e.g., [14] and [15]). Note that only the textual content is considered (embedded images are ignored).

| Size | |

|---|---|

| Min | 0 |

| Max | 524300 |

| 1st Qu. | 2307 |

| Median | 6935 |

| 3rd Qu. | 15990 |

| Mean | 12920 |

| Std. dev. | 24061.55 |

The language distribution was studied using n-gram based text categorization [4], as implemented by text_cat. The results shown concern the top 7 languages. It may be worth noticing that there is not even the faintest relation between this distribution and the African reality: for example, according to [12], the number of English native speakers is slightly more than 5,500,000, no more than 0.007% of the whole African population; French and Spanish are spoken by only 950,000 and 31,000 people, respectively.

| Language | % |

|---|---|

| English | 74.68% |

| French | 7.33% |

| Spanish | 5.57% |

| Afrikaans | 2.97% |

| German | 1.21% |

| Danish | 1.05% |

| Portuguese | 0.92% |

The high percentage of table-related elements, and in particular of TD elements of fixed width, suggests that tables are being used for layout purposes. The IMG element, which ranks just after the ubiquitous A element both in .it and .com, is much rarer in the African web, probably due to the low bandwitdh, which makes textual information preferrable. The percentage of IMG elements having an ALT attribute for accessibility is about 34.52% (for .com is about 44.32%).

|

|

|

|

Scripting is comparatively less common in the African web (39.45% of the pages). The domains .com and .it sport a percentage of scripted pages of about 62.43% and 48.01%, respectively. The type of language is deduced from the deprecated LANGUAGE attribute, except for text/javascript, which is deduced from TYPE.

|

|

Coherently with the predominance of IIS among servers, the most common extension among child URLs is .asp. Static pages follow, and then PHP dynamic pages. Some data about image types in child URLs: JPG 68.06%, GIF 31.30%, PNG 0.55%.

|

|

The distribution of protocols is very similar to the one typically observed for other domains, except for the low occurrence of the https protocol.

|

|

To study the indegree and outdegree distribution of the African Web graph, we have performed some statistical evaluations, computing, for instance, extremals, quantiles and mean. One immediately notices that the max in-degree is characterized by very high figures, associated with a large standard deviation. A human inspection of the collected URLs revealed that this comes from the presence of many "portal sites" and "directories", which link to some popular URLs from different points of their hierarchy. As expected, such a phenomenon is less relevant for the outdegree distribution.

| In-degree | Out-degree | |

|---|---|---|

| Min | 0 | 0 |

| Max | 23660 | 1975 |

| 1st Qu. | 1 | 1 |

| Median | 2 | 6 |

| 3rd Qu. | 4 | 17 |

| Mean | 13.32 | 13.32 |

| Std. dev. | 117.53 | 24.12 |

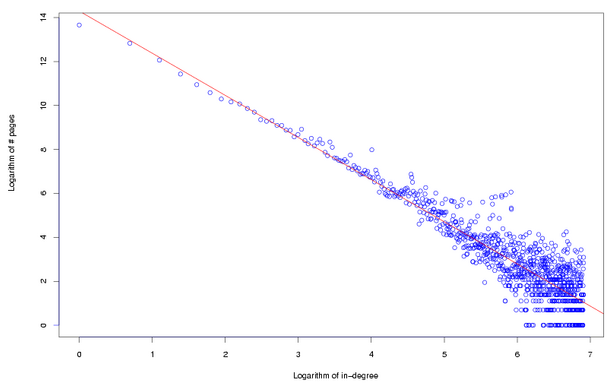

It is observed that in-degrees of web pages typically follow a Power Law distribution [8, 9, 10]. This means that the number of URLs with i in-links is proportional to iα for some constant α < 0. The analysis of the data collected for the African web gives futher evidence to such observation. After discarding all the pages whose in-degree exceeded 1,000, we have computed some figures which led to an estimate of -1.92 for α.

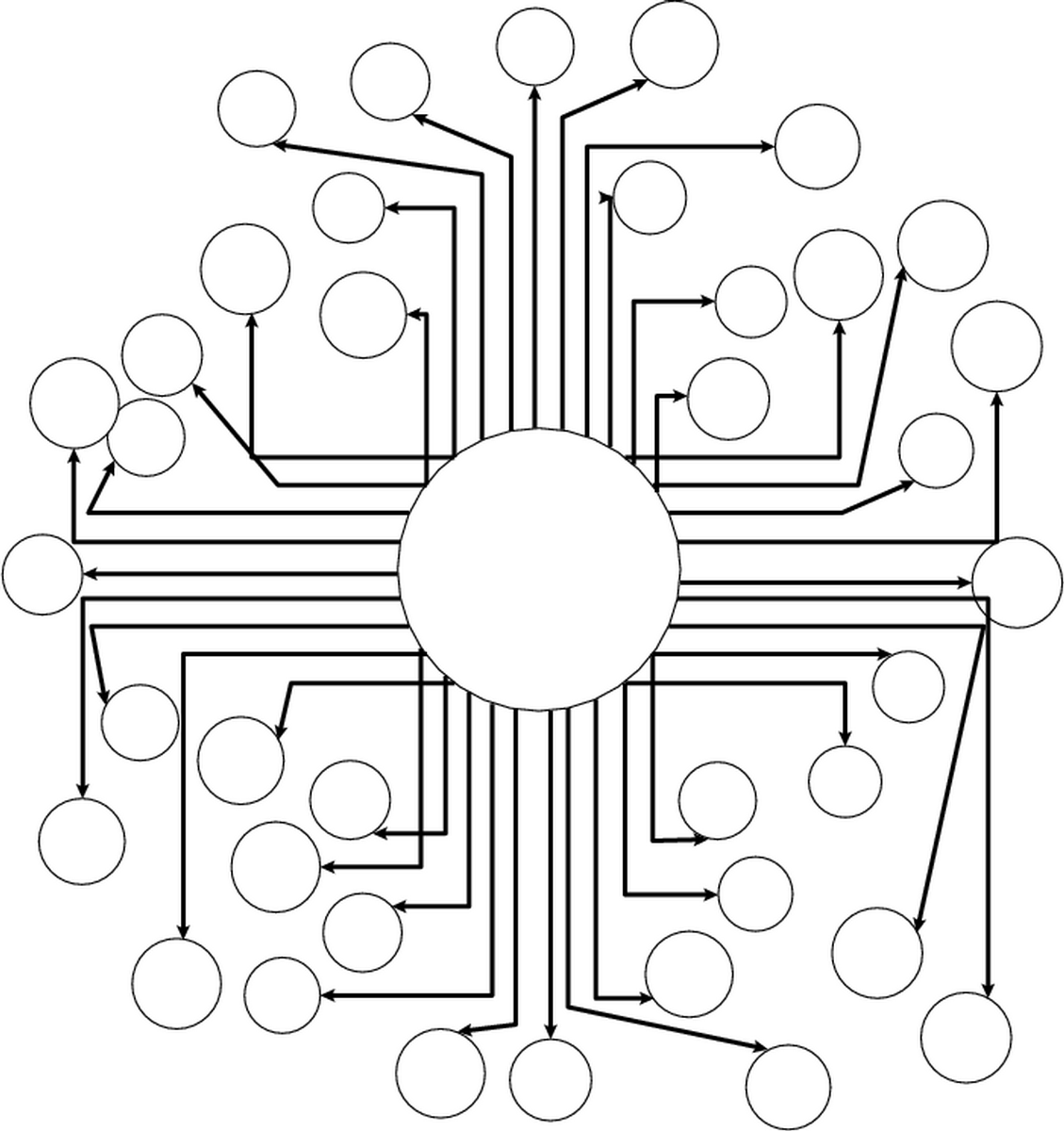

The graph structure of the African web presents some differences from the "bowtie theory" [7]. Half of the pages we have downloaded are condensed into a single giant strongly connected component, pointing to several smaller components. We have no evidence regarding components pointing to the giant component, possibly because of our seed choice. Nonetheless, the size of the main component is much larger than usually observed for the Web, possibly because most sites are from South Africa (suffix .za), and regional web sites tend to be more connected.

| w/ singletons | w/o sinlgetons | |

|---|---|---|

| Max | 977300 | |

| 1st Qu. | 1 | 3 |

| Median | 1 | 6 |

| 3rd Qu. | 1 | 13 |

| Mean | 3.33 | 85.8 |

| Std. dev. | 1274.85 | 7696.56 |

The poor connectivity properties observed in [2] are confirmed by our experiments; indeed, with the exception of a large number of links from Namibia to South Africa, and some interconnection between Morocco and Senegal, the African web graph is largely disconnected, and presents a high degree of internal connection within each state (represented by a specific suffix).

| No. of pages | .za | .ma | .tn | .eg | .na | .zw | .sn | .mz | .ly | .com | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| .za (South Africa) | 1609722 | 25670617 | 72 | 11 | 121 | 782 | 585 | 40 | 133 | 3366 | 1355982 |

| .ma (Morocco) | 64942 | 27 | 681366 | 32 | 132 | 1863 | 3 | 4 | 1 7299 | ||

| .tn (Tunisia) | 47904 | 3 | 77 | 383543 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 70 01 | |||

| .eg (Egypt) | 41780 | 14 | 4 | 1 | 437665 | 8169 | |||||

| .na (Namibia) | 25122 | 5595 | 7 | 355565 | 11 | 5 | 5406 | ||||

| .zw (Zimbabwe) | 24631 | 185 | 2 | 4 | 534892 | 3 | 25983 | ||||

| .sn (Senegal) | 23184 | 70 | 2751 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 210301 | 1 | 5797 | |

| .mz (Mozambique) | 11564 | 445 | 2 | 11 | 1 | 177031 | 30528 | ||||

| .ly (Libya) | 10876 | 18 | 138616 | 7263 |

Putting Africa on the Web was a goal of the early 90's, with several organizations involved in the process. As already mentioned, a status report on the growth of the African Web come out in 2001 [2], which indicated trends and properties of the growth of Internet usage in Africa. This poster has provided a complementary view of the African Web, in terms of both structure of the pages and most used technologies, and structural properties of the African web graph.

The main evidences emerging from our analysis are significant departures from known properties of the web graph in terms of connectivity and the widespread use of mature technologies.

We plan to periodically refresh our information in order to keep track of the evolution of the African web graph, and in particulat to analyze how its connectivity changes over time.