representation of

pyramidal image

representation of

pyramidal image

aMultimedia Research Group, Department of Electronics and Computer

Science,

University of Southampton, Southampton SO17 1BJ, UK

bThe National Gallery, Trafalgar Square, London, UK

The Viseum project [6], due to finish in March 1998, aims to allow network access to these images. There are three key components: a small, easy-to-use colorimetric network image viewer (an X11 GUI has been used for some time [7] inside the National Gallery but this is not suitable for general Intranet/Internet use), a central indexing system to allow searches for images across all Viseum sites, and a security and billing server to control access. Access control is important, since the sale of images of this quality to publishers currently generates considerable income for galleries.

Each site in the project has a CD-ROM jukebox (from NSM [8]), a database, and a Web server. Sites in London, Paris, Berlin and Vancouver are connected to each other and to the central index and security servers via an ATM test-bed TCP/IP network. This provides a private channel of up to 6Mbit/s which will be used to tune the client–server design.

This paper will concentrate on the high resolution image server and

client.

SRGB does not allow the representation of colours outside the standard monitor gamut, a problem for many paintings. IIP provides a set of protocols for querying the image server and obtaining images, possibly processed at the server. At the moment a server exists for NT and clients can be based on ActiveX or Java. and we have made rather different design choices:

Instead, we are using the freely-available IJG JPEG library, combined with a standard libtiff package. Tiled JPEG-in-TIFF is already a standard file format: we just add extra sub-images for the layers in the pyramid, and save pixels as LAB rather than RGB. The resulting images can be read by many standard TIFF viewers (the viewers which come on SGI machines, for example), although unfortunately not with current versions of Photoshop, since it does not yet support JPEG TIFF.

Low compression factors (less than 10:1) provide visually lossless images suitable for browsing. Here we typically use a compression of around 6 times. Each tile is decodable singly and is ideal for network transmission. There is no inter-resolution compression as in Photo-CD, as this makes decoding much slower. However this means that to boost performance our format stores a third as much information as a compressed large file.

representation of

pyramidal image

representation of

pyramidal image

Each pel is an 8:8:8 bit Lab value. Images from the National Gallery are originally 10:11:11 bits for a fine quantisation of colour space but 8 bits per channel is sufficient for display purposes. The final TIFF file contains all the levels of the pyramid, stored sequentially.

For comparison the SCOPYR format [11] used in the Louvre has a fixed,

large tile size of 800x600 and stores each tile in a separate file with

a three letter name extension related to the tile position.

The image server is linked to a standard Web server with FastCGI. A typical request might look like:

| file | The name of the file from which tiles should be fetched. |

| session | The session cookie for this client. The cookie is used for authentication, and to retrieve the user's preferences, such as their display type. |

| x, y, w, h | The size and position of the tile the client needs. This does not have to match the tile sizes and boundaries used in the actual image. |

| sub | The amount of sub-sampling to apply to the original image before transmission. This has to be a power of two. |

| ht, vt | Horizontal and vertical repeat. The server repeats the x, y, w, h |

As each tile request is a separate CGI call to the server, FastCGI is used for efficiency and to maintain state information, particularly a cache. Recently requested tiles are cached, which is especially useful if the server does all of the processing. The CGI is written in C, as is the VIPS [7] image processing library used for any colour processing. This has the added advantage of automatically using parallel CPUs on multiprocessor systems.

The CD Jukebox from NSM stores 150 CDs and presents them as directories under Unix. It has four 12x speed CD drives and its driver uses a hard disk cache. The CD swap time is only 4 seconds, but this combined with the 4 drives means the hard disk cache is important for serving more than 4 clients. Eventually a large cache would build up the typical areas of popular images such as faces, hands etc. If the complete National Gallery collection was stored with an average file size of 100 MBytes, the approximately 2000 works would fill over 300 CDs and two jukeboxes. In contrast the Louvre scans at lower resolution but more images per work and has already filled two jukeboxes. In the next two years the jukeboxes will be upgraded to DVD media (3.6 GB) and one jukebox would store the National Gallery collection. DVD would also allow uncompressed images to be stored, which can be too large to fint onto one CD-ROM.

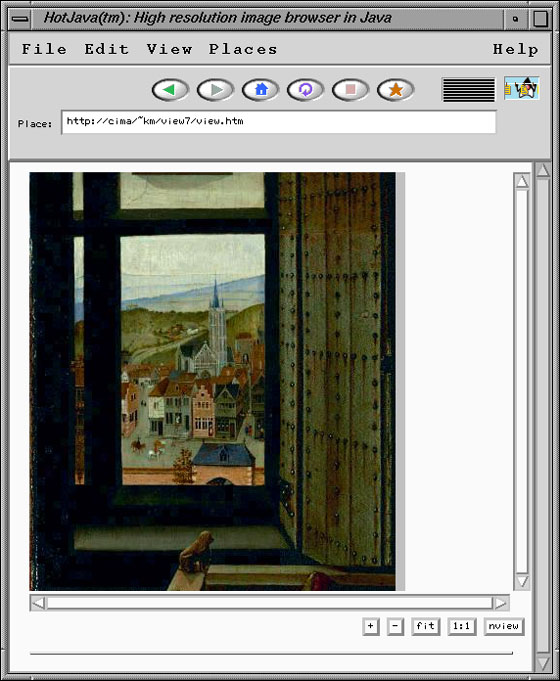

Fig. 1. Applet viewer in HotJava. Full image, from the National Gallery

in London, to Southampton.

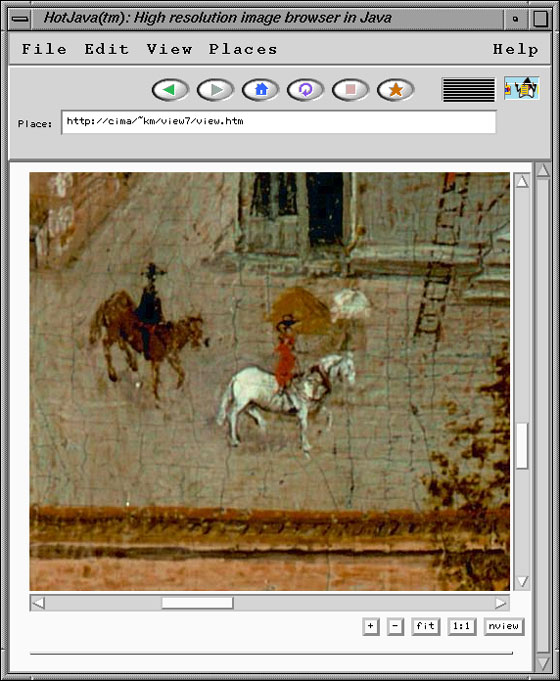

Fig. 2. Browsing highest resolution image.

An existing monitor profiling system made by Colorific [13] is used to generate the ICC for the user's monitor. This is a Web site which provides a procedure of selecting colour patches on-screen and using a small blue, plastic test-pattern as a mask. The resulting colour profile (ICC [14]) is used to convert from colour spaces to display RGB. More accurate techniques require a measuring instrument, which most users would not have. Results across different monitors are promising.

We have put quite a lot of effort into tuning the display parts of the

client: image display is fully threaded, so the interface stays ``live'',

even during heavy network access; and is interruptable, so it is not possible

to build up a large queue of pending requests. The just-in-time compilers

for Java seem to be fast enough to do image handling at the client, with

a short but noticeable slow-down on start-up.

The overall client–server communication can be summarized as follows:

|

|

|

| request image info | get image info and send |

| request area of image

|

read tiles

decompress JPEG Lab to RGB compose into one image if needed compress to JPEG send data |

| decompress JPEG and display |

|

|

|

| request image info | get image info and send |

| request area of image | read tile

decompress JPEG send Lab data uncompressed |

| Lab to RGB

display |

The size of the requests made by the client affect throughput because of the overhead of setting up HTTP requests for more, smaller tiles for example. Requests which are larger than a file tile require processing at the server to compose them into whole images, but in practice this is so fast as to be unnoticeable. However large tiles mean scrolling has long infrequent delays rather than short frequent delays.

Fig. 3. Time to repaint a 1500 x 1500 screen in seconds vs request image size, for server processing and mainly client processing colour. 100 Mbit/s network. 128 x 128 tiled image served from SGI Origin 200, displayed on SUN UltraSPARC.

The graph in Fig. 3 shows the effect of requesting various sizes of image from the server. The area repainted is equivalent to around 9 normal screens so that the times were more easily measured. When the server does the colour processing (srv proc), requesting images smaller than the file's 128x128 tiles leads to inefficiency and slow repaints. Larger requests seem to have lower overheads and hence faster repaints. The line for cached is where the server probably has the tiles in cache already, so it does little processing. With a fast client which simply has to de-JPEG this is the fastest set-up. The blue lines are for colour processing on the Java client and show that requesting the file's tile size of 128 is very efficient and that Java processing leads to little slow-down. The Java colour processing is a faster LUT-based operation, unlike the server-side arithmetic computation, so this may balance the slower speed of Java code.

With low bandwidth or busy network connections the bottleneck is clear and the time spent computing in the browser becomes less important. In contrast tests were carried out over a 100 Mbit/s LAN where the client performance becomes critical.

Tests were carried out with images being read from a 12X CD drive on

an SGI Origin 200. This provided fast browsing and file system caching

helped keep response times low for multiple clients. This suggests that

the cached Jukeboxes in use in the project will cope well as long as disk-swapping

does not become an issue.

[2] K. Martinez, J. Cupitt, D. Saunders, High resolution colorimetric imaging of paintings, in: Proc. SPIE, Vol. 1901, Jan. 1993, pp. 25–36.

[3] Beutlhauser, R., Lenz, R., A microscan/macroscan 3 x 12 bit digital color CCD camera with programmable resolution up to 20 992 x 20 480 picture elements, in: Proc. of the Commision V Symposium Close Range Techniques and Machine Vision, Melbourne, Austr., 1–4 March 1994, Intl. Archive of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, Vol. 30, Part 5, ISSN 0256-1840, pp. 225–230.

[4] Commission Internationale de l'Eclairage, Recommendations on uniform colour spaces, colour difference equations, psychometric colour terms, Supp. No. 2 to CIE Publication No. 15 (E-2.3.1), 1971 (TC-1.3), 1978.

[5] H. Chahine, J. Cupitt, D. Saunders and K. Martinez, Investigation and modelling of colour change in paintings during conservation treatment, in: Proc. of Imaging the Past, British Museum Occasional Paper No. 114, London 1996.

[6] Viseum project: http://www.InfoWin.org/ACTS/RUS/PROJECTS/ac238.htm

and

http://www.ecs.soton.ac.uk/~km/projs/viseum

[7] J. Cupitt and K. Martinez, VIPS: an image processing

system for large images, in: Proc. SPIE conference on Imaging Science and

Technology, San Jose, Vol. 1663, 1996, pp. 19–28;

also: http://www.ecs.soton.ac.uk/~km/vips/

[8] NSM, http://www.nsmjukebox.com

[9] FlashPix, http://wwww.kodak.com/drgHome/productsTechnologies/FPX.shtml

[10] sRGB, http://www.color.org/contrib/sRGB.html

[11] SCOPYR/JTIP, http://www.argyro.net/demo/avelem/jtip.htm

[12] J. Gosling, B. Joy, G. Steele, The Java Language

Specification,

Addison Wesley, Reading, MA, ISBN 0-201-63451-1, August 1996,

http://www.javasoft.com/doc/language_specification.html

[13] Colorific, http://www.colorific.com

[14] International Colour Consortium, http://www.color.org/