1. INTRODUCTION

In recent years we have seen the explosive growth of small Internet devices such as handheld computers, personal digital assistants (PDAs) and smart phones that have been used to leverage the capabilities of the Web and provided users with ubiquitous access to information than ever before. Despite the proliferation of these devices, their usage for accessing the Web today is still largely constraint by their small form factors such as small screen. Because most of today’s web page has been designed with the desktop computer in mind, and is often too large to fit into the small screen of a mobile device. Web browsing on such small devices is like seeing a mountain in a distance from a telescope. It requires the user to manually scroll the window to find the content of interest and position the window properly for reading information. This tedious and time-consuming process has largely limited the usefulness of these devices.

In order to improve the browsing experience, adaptation methods have been proposed to modify web contents to meet the requirement of client capability and network bandwidth [2–7,9–11,15]. In [6], methods were proposed for distilling web objects to reduce the consumption of network bandwidth and client computation. For web pages, the existing methods are mostly based on discarding format information. While this method mainly focuses on reducing resource consumption, there are still many works on beautifying the web page representation on small form factor devices. In [9], the web page is reformatted on the basis of page annotation. However, this approach requires a practical solution to facilitate the creation of annotations for existing web pages. The re-authoring technique proposed in [2] required web pages to have sections and section headers, which however, are rarely used in web page authoring today.

In the work of Buyukkokten et al. [3,4], an accordion representation is generated and the detail content can be folded or unfolded at client device. Since this method focuses on text summarization, it does not leverage the graphic capabilities of current devices. The SmartView [10] bears some similarity with our work in presenting adapted web page using zoom-in and zoom-out features.

1.1 A New Browsing Method

Our goal is to find a better way to enable easy navigation and browsing of a large web page on a small-form-factor device.

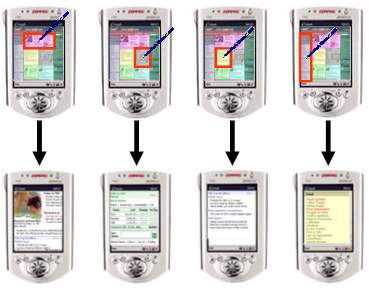

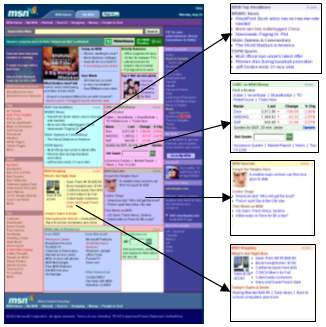

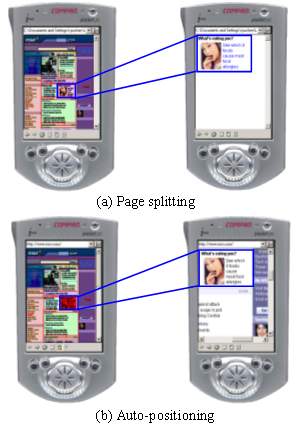

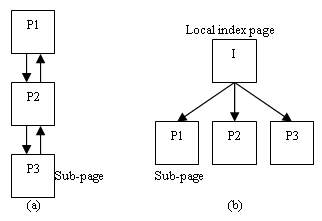

Figure 1. The idea of organizing a web page into a two level hierarchy with a thumbnail representation for providing a global view with each block of semantically related content represented by a different color. By clicking on a block in the thumbnail, a user can easily go to view the corresponding content which is formatted to fit well into a small screen.

Our major idea is to provide an overview of the web page and allow the user to select a desired portion of the web page to zoom in for detail reading (as shown in Figure 1). The overview is like a Table of Content (TOC) for the original web page. Instead of using traditional text based TOC, we provide a thumbnail on which each block of semantically related content is represented with a different color. By clicking on a block in the thumbnail, a user can easily go to view the corresponding content which is formatted to fit well into a small screen. Figure 1 shows the process of this browsing convention.

In this paper, our major contributions are:

- A novel idea of enabling easy browsing of a large web page on a small screen device is proposed.

- A comprehensive page layout analysis algorithm is proposed to detect the structure of an existing web page.

- The proposed method has been implemented and tested on a large set of web sites and pages to prove its applicability.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the overview of our approach. Section 3 presents the detail of page analysis algorithm. Section 4 introduces the web page adaptation method. Section 5 provides the performance evaluation of our approach and describes the auto-positioning method. We conclude our work in Section 6.

2. OUR APPROACH

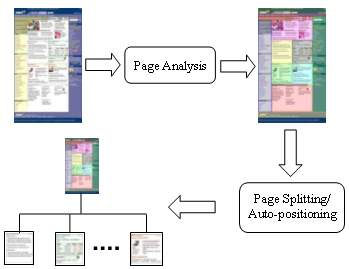

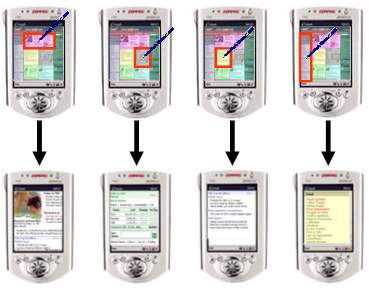

In order to enable the new browsing method described in Section 1.1, there are two technical problems we need to solve. One is how to detect the semantic structure of an existing web page, and the other is how to split a web page into smaller blocks based on the detected structure. Therefore, our approach for web page adaptation consists of two processes as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Our approach for web page adaptation consists of two processes. The first process analyzes the structure of a give web page, and the second process splits the web page into a two-level hierarchy. For a web page not suitable for splitting, an auto-positioning method (or scrolling-by-block) is used to provide a similar user experience.

The first process performs a page analysis to extract the semantic structure of a web page. From the extracted structure, different content blocks are identified. In the second process, the web page is split into many sub-pages according to the structure information. For a given web page, a thumbnail is generated at the top level and served as the navigational entry for all the sub-pages at the bottom level. In case that a web page is not suitable for splitting, an auto-positioning method or scrolling-by-block is used to provide a similar user experience without physically breaking up the original web page.

3. PAGE ANALYSIS

The goal of page analysis is to extract the semantic structure of an existing web page. This structure is a hierarchical representation of the web page, in which each node is a group of objects in the web page. A node at a higher level of the hierarchy tends to contain multiple objects with different information while a node at a lower level tends to contain a single or a small number of objects that is a part of an information unit. The goal of our page analysis is to identify a set of nodes in the hierarchy, in which each represents a unit of information that can be managed and displayed individually as described in Section 1.1. These nodes are called “content block” in the rest of this paper.

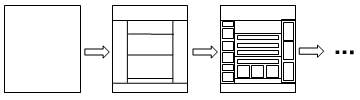

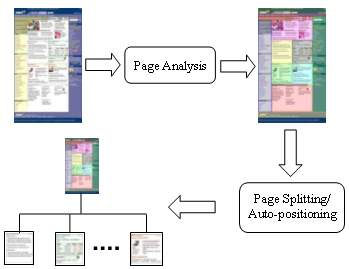

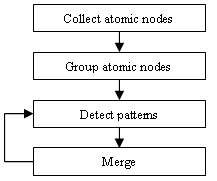

In our approach, identifying the content blocks from the semantic structure of a web page is conducted in an iterative manner. At the beginning, the whole web page is regarded as a single content block. At each iteration, the page analysis algorithm finds a best way to partition a content block into smaller ones. A set of content blocks will remain at the end of the process, which serves as the final information for page splitting. Figure 3 shows this process.

Figure 3. The process of identifying the content blocks is performed in an iterative way. It starts with the whole web page as a single content block, and then iteratively partitions each content block into smaller ones until the process reaches the final solution.

The final solution is dependent on the information contained in a web page and can be derived by semantic analysis. However, today’s natural language technology is still far from delivering a satisfactory result. Our approach is to perform the analysis by inferring the content structure of a web page embedded by the web author.

3.1 Content Structure Embedded by the Web Author

When the author creates a web page, he in general either uses a template or has a page layout in mind to guide his design. For example, he may consider whether to put a header, footer, or side bars in the page, and decide how many distinct topics in the body. Although such a high-level content structure usually disappears after the web page is constructed and sent to the client, it is possible to recover this content structure based on the clues the author embeds in the web page.

The author often creates a partition of content with visual separators. Two kinds of visual separators are commonly used. Explicit separators are created using certain HTML tags. Implicit separators are created by leaving a blank space between content in a web page.

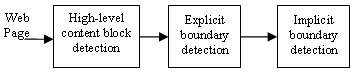

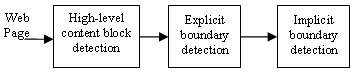

Figure 4. The three-step processing in our web page analysis algorithm

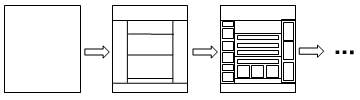

Our page analysis algorithm consists of the following three steps: first, we analyze the HTML DOM tree and detect the high-level content blocks about the locations and sizes of header, footer, side bar and body; then we analyze the content inside each high-level content block to identify explicit separators to split the content blocks; lastly, implicit separators are detected and used to split the content blocks further. The whole process is shown in Figure 4.

3.2 High-Level Content Block Detection

When designing a web page, the author usually produces a scaffold or template to guide the page design. The scaffold or template is the high level structure of a web page. Layout related tags are often used to produce a scaffold or template.

In most cases, a scaffold would contain one or more of the following blocks: header, footer, left side bar, right side bar and body. Extracting the high-level content block is to determine what content falls into which high-level block. For any given content, we can decide which block it should belong to by analyzing the position and shape of the region it occupies. For instance, content in header and footer usually has a flat shape (i.e. small height/width ratio), while header content locates on the top of a web page and footer content locates on the bottom.

3.2.1 Selecting Nodes

We first use an HTML parser to generate the HTML DOM tree which also gives the position and dimension information for each node in the DOM tree.

Then the DOM tree is traversed from <BODY> to its leaves to select appropriate nodes and put them into a corresponding high level content block. Selecting appropriate nodes is first conducted by deciding whether it is better to keep a node as a unit or move one level down to consider its child nodes as units. If a node is too large, keeping it as a whole will produce erroneous results. For example, in the Yahoo! home page, the <BODY> contains a single child node <CENTER> which is used to align all the content to the center of the page. If the node <CENTER> is kept as a whole, we will not be able to detect its header and footer.

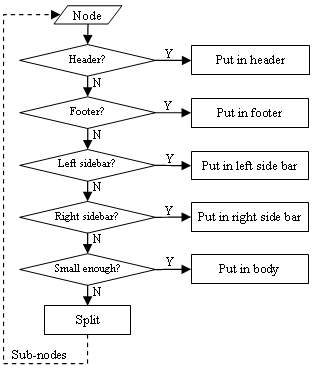

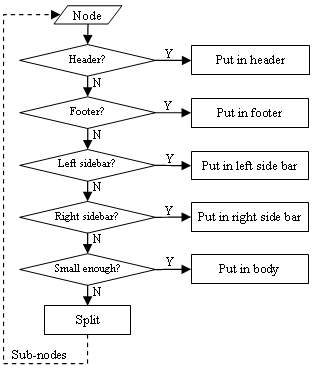

Figure 5 shows the algorithm for selecting nodes. We try to classify a node into one of the header, footer, left side bar and right side bar blocks. If it belongs to none of the above, then we check if it is small enough to put into the body block. A pair of thresholds (one for width and the other for height) is used to determine whether a node is small enough. If the node exceeds the thresholds, it will be split further. The above process is iterated until all the nodes are classified into the five high-level blocks.

Figure 5. Selecting appropriate nodes and classifying them into one of the five high level content blocks

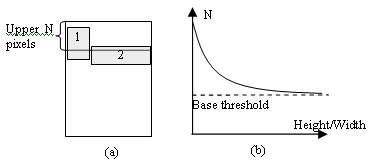

3.2.2 Detection of Header and Footer

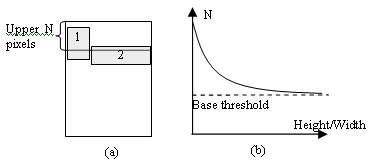

Since the header block locates on the top of a web page, it is intuitive to define a threshold N and let the upper N pixels of a web page be the header region. If the region rendered by a node is inside the header region, the node is classified into the header block. Then the problem becomes how to select an appropriate value for N. The challenge for selecting an appropriate N is illustrated in Figure 6(a). In this figure, the regions of two nodes overlap with the upper N pixels, and the node #1 does not belong to the header block while the node #2 does. In this case, we can not exclude the node #1 while trying to include the node #2 by increasing the threshold N since the bottom of the node #2 is lower than that of the node #1. To solve this problem, a dynamic threshold based on the height/width ratio of the shape of the region of a node is used. The smaller the ratio is, the bigger the threshold is. Therefore, a node with flatter region will have a higher possibility to be put into the header block.

Figure 6. Dynamic threshold for header and footer detection

Figure 6(b) shows the desired curve for the dynamic threshold which is approximated by letting N = base_threshold + F(Height/Width) where F(x) = a/(b*x+c) and base_threshold, a, b and c are constants. In our experiments, we found that the best performance can be achieved by setting base_threshold = 160, a = 40, b = 20, and c=1. A similar approach is also used for classifying nodes to the footer block.

3.2.3 Detection of Left and Right Side Bar

The detection of left and right side bar is similar to the header and footer. Since a side bar region depends on the width of the web page, the threshold needs to be adaptive too. In our experiments, we define the left 1/4 part of a web page to be the left side bar region, and right 1/4 part to be the right side bar region. The shape of the region of a node is not taken into account because the left and right side bars usually contain several small regions which are not slim in many cases.

Figure 7 shows the result of high level content block detection for Microsoft’s home page. The blocks are represented by different colors.

Figure 7. The result of high level content block detection on the Microsoft’s home page

3.3 Explicit Separator Detection

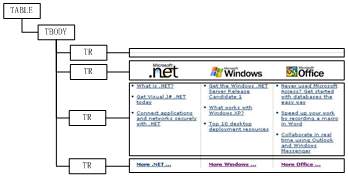

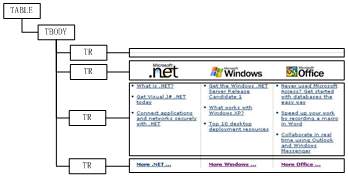

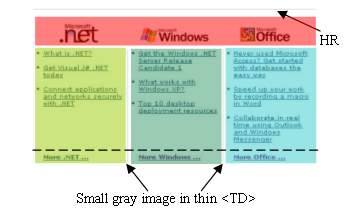

The algorithm described in Section 3.2 is used to detect the high-level content blocks. We could apply explicit separator detection to further partition them. For example, the third node in the body block as shown in Figure 8 contains three columns that can be further segmented for easy browsing.

Figure 8. The DOM structure of the third node in the body block in Figure 7

Explicit separators can be detected by analyzing the properties of the tags. The following three types of explicit separators are widely used:

- <HR> is the most frequently used explicit separator for representing a horizontal line in a web page.

- The tags such as <TABLE>, <TD> and <DIV> have border properties. When their border properties are set, there would be separators at the corresponding borders.

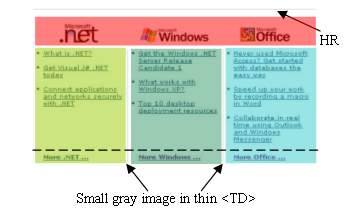

- The third type of explicit separator is created using an image. For example, in Figure 9, the gray vertical lines that separate the content into three columns are images embedded in very thin table cells. This type of separator can be detected by analyzing the width and height of embedded images.

By analyzing the above three types of explicit separators, the content in Figure 8 is partitioned into 4 sub-blocks and the result is shown in Figure 9. As can be seen, the upper one contains the icons. The three icons are placed in one block because they are contained in a single image which can not be segmented further. The lower part is divided into three columns.

In the next section, we will discuss the implicit separator detection to divide each column further into two parts (as indicated by the dashed line in Figure 9).

Figure 9. The explicit separator detection

3.4 Implicit Separator Detection

Implicit separators are blank areas created intentionally by the author to separate content. Because they cannot be directly detected by analyzing the HTML DOM nodes, special techniques have to be developed.

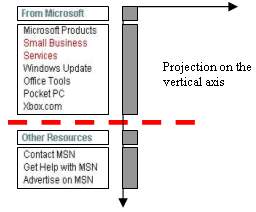

As these implicit separators are blank areas in a web page, we develop a method to them by

- first collecting all the basic content blocks inside each high-level content block after explicit separator detection;

- and projecting each basic content block along the horizontal and vertical axes to generate projection diagrams;

- and based on the diagrams, the widest gap on each axis is selected as an implicit separator to partition the block into smaller ones;

- The previous process is iteratively applied to the small blocks until no implicit separator is detected.

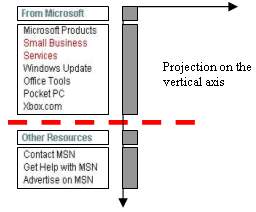

Figure 10 shows an example containing a fragment from MSN home page which contains four basic content blocks. By projecting them onto the vertical axis, the diagram is generated. Zero projection value on the diagram indicates a possible implicit separator. As can be seen, the biggest gap will partition the fragment into two blocks and the other two smaller gaps will be detected to divide each of the blocks further.

Figure 10. Detecting implicit separators

Because the implicit separator detection is based on the projection of basic content blocks onto the vertical and horizontal axes, the size of basic content block is critical to the precision of detection. Big content blocks may fail to reveal fine boundaries while small blocks may produce more noise.

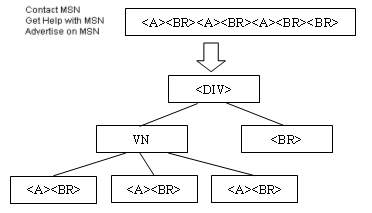

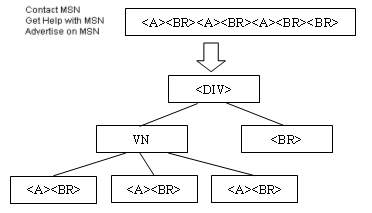

Figure 11. Detection of basic content block by pattern recognition and clustering. VN represents a virtual node.

To resolve the problem, a method similar to that in [16] is used to produce the basic content blocks. For example, the fourth content block in Figure 10 is a <DIV> containing a sequence "<A><BR><A><BR><A><BR><BR>". It is obvious that the "<A><BR>" is the most frequent pattern appearing in the sequence and can be grouped together. Then the three small groups can be merged into a virtual node VN. Now the structure inside the <DIV> becomes a form shown in Figure 11. The virtual node VN is considered the basic content block since the last <BR> represents an empty line.

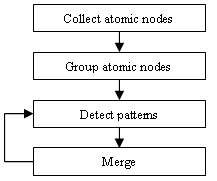

Figure 12. The pattern recognition algorithm is used to produce basic blocks for implicit separator detection.

The pattern recognition algorithm is shown in Figure 12 and works as follows. First, we define an atomic node to be a leaf node or a special tag such as the tag <A> since it denotes a hyperlink and <MARQUEE>, <SELECT> and <MAP>. If a leaf node is a text node and is the only child of its parent tag, it will be selected as the atomic node. All the atomic nodes in the HTML DOM tree are collected and arranged in the same order as they appear in the HTML code.

A similarity measure based on text font, size, color, and tag properties is applied to cluster the atomic nodes into groups. We denote the atomic nodes of the same group with a same symbol, changing the node sequence into a symbol string. From the string, we detect all the possible patterns (sub-string) and compute their frequency in terms of times of appearance in the string. Among the patterns with highest frequency, we select the longest one and group the pattern using a new symbol if its length is larger than 1. If the length is equal to 1, we try to merge it with the adjacent symbols. If no merge can be made, the pattern with the next highest frequency will be selected. The same clustering method is applied on the newly created string at each iteration until the highest frequency is below a certain threshold.

We define a blank symbol to be <BR>, space characters, blank <TD> (i.e. <TD> containing space characters only), <MAP> or <SCRIPT>. Except these blank symbols, each symbol in the last string represents a visual unit VN for implicit separator detection.

4. PAGE ADAPTATION

The major problem for browsing a large web page on a small screen is horizontal scrolling. A wide text body is often cut in half and requires constant horizontal scrolling for reading. Our page adaptation tries to resolve this problem by splitting a large web page into smaller sub-pages that fit well into the small screen of a mobile device.

We consider two methods for splitting a web page: the first is called single-subject splitting; and the second is called multi-subject splitting.

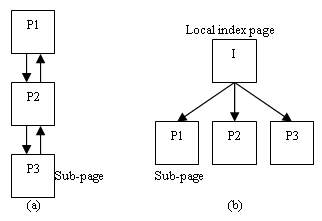

Single-subject splitting breaks the whole web page into several sub-pages and connects them with next/back hyperlinks. When browsing an adapted web page, the user will access each sub-page one by one in the defined sequence. Figure 13(a) shows this scheme.

Figure 13. (a) Single-subject splitting. (b) Multi-subject splitting.

Multi-subject splitting generates a new index page in addition to sub-pages. The index page contains hyperlinks pointing to each sub-page. So the result of multi-subject splitting is a two-level hierarchy of content as shown in Figure 13(b). While browsing an adapted web page, the user will first receive an index page. This index page provides an overview and guidance for the user to access each sub-page through the hyperlinks in the index page.

Single-subject splitting is suitable for a web page which contains the content of a particular topic, such as a news story in the MSNBC web site. Multi-subject splitting is more appropriate for the homepage of a web site. In this paper, we use multi-subject splitting as an example to illustrate our page adaptation technique.

4.1 Page Splitting and Sub-page Generation

Before conducting page splitting, we need to determine the appropriate size of block so that it is smaller than or equal to the screen size. Based on the result of page analysis, the content in the final set of content blocks can be easily extracted and stored into sub-pages.

Some content cannot be put into a sub-page directly because of the problems of style and hyperlink. In the following, we discuss how to resolve each of these problems.

4.1.1 Dealing with Style

HTML standard permits the author to use Cascading Style Sheet (CSS) [12] and style inheritance to specify content style. CSS allows the author to define the style of a tag, a tag class or tag instance. Style inheritance allows the author to specify a node’s style at one of its parent nodes. Extracting content from a block of HTML file may lose some style information because the style information from CSS and inheritance is not located together with the content.

In order to keep the original appearance of a block, we need to retrieve its style information. For the CSS case, since CSS is usually specified in <HEADER> using <STYLE> or <LINK>, we could copy the <HEADER> section of a web page into each generated sub-page.

For the case of style inheritance, we must trace along the parent link of a target node and retrieve all the style information of each parent tag. The style information of each tag along the link is merged. Whenever there is a conflict, a child tag will overwrite its parent tag.

4.1.2 Dealing with Internal Hyperlinks

Internal hyperlinks are often used to assist a user to locate content inside a web page. For example, <A id=“id1”>…</A> is used to specify a place in a web page. Then <A href=“#id1”>…</A> can be used as a pointer to the specified place. When clicking on an internal hyperlink, the browser will scroll directly to the specified location.

After a web page is split into several sub-pages, the place specifier and the pointer may appear in different sub-pages. For example, <A id=“id1”>…</A> may appear in sub-page-1.htm while <A href=“#id1”>…</A> appears in sub-page-2.htm. Our solution is to change the pointer in sub-page-2.htm to <A href=“…/sub-page-1.htm#id1”>…</A>. The page splitting module is responsible for searching the internal hyperlinks and making appropriate modification.

4.1.3 Dealing with Relative Hyperlink Resolution

The author can specify an absolute hyperlink or a relative hyperlinks in <A> and <AREA>. The Web browser resolves relative hyperlinks to absolute ones according to the base URL of the web page. The default base URL is the URL of the web page. But the author can override the base URL using <BASE> tag. The <BASE> tag resides in the <HEADER> section, which is another reason of copying the <HEADER> section into each sub-page.

4.2 Index Page Generation

An index page which contains a thumbnail and hyperlinks to its sub-pages will be generated after all the sub-pages are created. We first generate href values based on the names of the sub-pages. For example, we could name each sub-page in the form of origin_xxx.htm, where origin denotes the name of the original web page and xxx denotes the number of a sub-page.

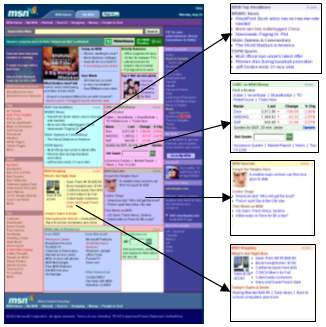

We generate a thumbnail image for the original web page, and mark the content blocks with different colors. Then we put an <IMG> tag to reference the thumbnail image and corresponding <MAP> tag in the index page (A <MAP> tag contains a hyperlink to a sub-page.). While browsing an index page, the user can click on any block in the thumbnail to access the corresponding sub-page. Figure 14 shows an example of the index page and sub-pages generated from the homepage of MSN.com.

Figure 14. Page splitting for the homepage of MSN.com

5. Experimental Results

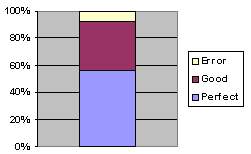

We conducted some experiments to evaluate the performance of our algorithm. To perform the experiments, we selected 50 popular web sites and 200 typical web pages from them as our test data. Each web page is adapted using our algorithm and the result is evaluated by testers to put into one of the following three categories: perfect, good and error. Perfect means that the page analysis and splitting is perfect without any error. Good means that the page analysis result is correct but there are minor errors in page splitting and those errors do not affect the viewing of the result. Error means that there are errors in both page analysis and splitting processes, causing a browsing problem or losing some information.

Table 1. The 50 tested web sites and the corresponding results

| Web Site | Perfect(%) | Web Site | Perfect(%) |

|---|

| Yahoo.com | 60% | Msnbc.com | 17% |

| Msn.com | 50% | Jobsonline.com | 0% |

| Aol.com | 60% | Flowgo.com | 100% |

| Microsoft.com | 20% | Earthlink.net | 25% |

| Altavista Search Services | 80% | Americangreetings.com | 75% |

| Passport.com | 75% | Ivillage.com | 100% |

| Hotmail.com | 60% | Mypoints.net | 100% |

| Go.com | 80% | Cnn.com | 20% |

| Netscape.com | 0% | Goto.com | 0% |

| Amazon.com | 60% | Bizrate.com | 75% |

| Excite.com | 40% | Mapquest.com | 67% |

| Nbci.com | 100% | Passthison.com | 0% |

| Ebay.com | 80% | Weather.com | 75% |

| Bluemountain.com | 80% | Mo.net | 50% |

| Lycos.com | 0% | Collsavings.com | 100% |

| Real.com | 60% | Infospace.com | 100% |

| Looksmart.com | 80% | Iwin.com | 60% |

| Cnet.com | 80% | Espn.com | 0% |

| Angelfire.com | 40% | Colonize.com | 25% |

| Tripod.com | 80% | Travelocity.com | 75% |

| Askjeeves.com Search & Services | 80% | Windowsmedia.com | 0% |

| About.com | 100% | Women.com | 0% |

| Speedyclick.com1 | N/A | Disney Online | 33% |

| Iwon.com | 60% | Zmedia.com | 100% |

| Zdnet.com | 80% | Google.com | 50% |

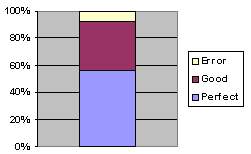

Table 1 shows the list of 50 tested web sites and the corresponding results. The number shows the percentage of perfect cases in each web site. Note that this is a very strict criterion, and we achieved 55% in average among these web sites. Figure 15 shows the distribution of our performance evaluation based on the three categories. Note that more than 90% of our results are either perfect or good.

Figure 15. The distribution of the performance evaluation based on the three categories: perfect, good, and error.

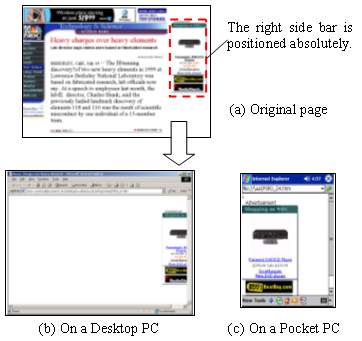

Most of the splitting errors in the category of “Good” are related to styles (including CSS), absolute positioning, or scripts used to display dynamic menus. When browsing a web page on a mobile device, these errors usually do not affect the viewing because most of these features are not supported by mobile browsers.

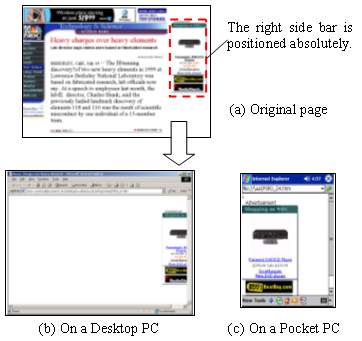

For example, a web page from MSNBC uses absolute positioning to place its right side bar, as shown in Figure 16(a). Although the right side bar is correctly detected and put into a sub-page, its position information causes a problem in display on desktop PC, as shown in Figure 16(b). But fortunately on a mobile device such as a Pocket PC, the absolute positioning is ignored by its web browser, so the result still looks fine, as shown in Figure 16(c).

Figure 16. The problem caused by absolute positioning of the right side bar in (a). When the corresponding sub-page is shown on a desktop PC, its position information causes a problem as shown in (b), but fortunately most mobile browsers will ignore the information, so the result on these small devices would still like fine as shown in (c).

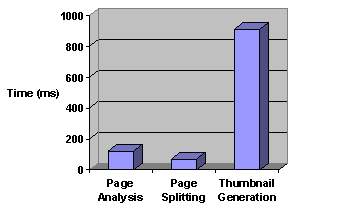

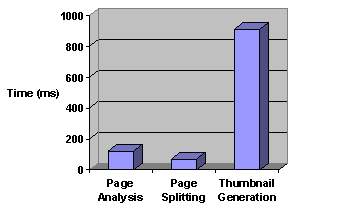

We also evaluate the processing requirement of our algorithm. Figure 17 shows the computation time for the three major processing in our algorithm. The experiment was conducted on a personal computer with 1.7 GHz CPU and 512M main memory. The result is shown in millisecond. The page analysis and splitting processing together take no more than 200 milliseconds. The thumbnail generation is slow because we currently use screen copy to obtain the image of the entire web page.

Figure 17. Processing time for our page adaptation algorithm

5.1 Further Analysis of the Results

In the following, we further discuss some of typical errors happened in our experiment.

5.1.1 HTML Syntax Error

In the page analysis stage, HTML syntax errors left by the author could cause the html parser to produce erroneous HTML DOM tree, which could sometimes make the high-level content block detection produce unexpected results. For example, a pair of misplaced <FORM> and </FORM> in a web page causes our parser to place the footer of the web page under a small table in the body. Consequently, the high-level analysis failed to detect the content in the footer and produced an incorrect result.

5.1.2 Side Effects of Splitting

Splitting a large web page into smaller sub-pages could decrease client loading time if it fetches only a few interested sub-pages. However, the presentation of a sub-page sometimes could look slightly different from what it appears in the original web page. For example, the home page of Lycos (www.lycos.com) uses an <IFRAME> as its header with width set to 100% and scrolling set to no, which means its width is equal to its parent tag. After splitting, the parent tagĄ¯s width is decreased, making the content in <IFRAME> clipped. Since <IFRAME> does not has scroll bars (scrolling property is no), the user cannot browse the content which is clipped due to the smaller width.

Another side effect is related to scripts. For example, some web pages use scripts to create dynamically scrolling text (e.g. www.netscape.com). After splitting, a script and the text it controls could be stored into two different sub-pages because they are located far away from each other in the original web page. As a result, the sub-page containing the script produces incorrect result while the text in the other sub-page cannot scroll.

5.2 Auto-positioning instead of Splitting

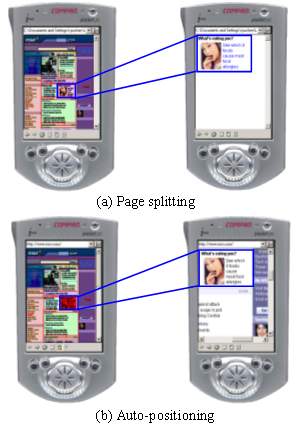

Figure 18. The comparison of web page adaptation using (a) page splitting and (b) auto-positioning

Since scripts tend to create inter-dependencies among the different part of a web page, they are problematic for splitting. For a web page that uses scripts extensively, it is better not to split it. Instead, assisting the user in scrolling the page is another direction to go.

Auto-scrolling is a scheme that positions the viewing window automatically based on the page layout information detected by our algorithm. The difference between this approach and the previous one is that the original web page is viewed when the user clicks on a block in the thumbnail view. That is, the browser switches back and forth between the thumbnail and orignal web page to provide the scrolling-by-block function. This method generates a very similar user experience to the page splitting method. Figure 18 shows the comparison of web page adaptation using page splitting and auto-positioning.

6. CONCLUSIONS

In this paper, we proposed a new method for facilitating the browsing of a large web page on a small screen. A web page is adapted and converted into a two level hierarchical organization with a thumbnail page at the top level for providing a global view and index to a set of sub-pages at the bottom level for detail viewing. We developed a page analysis algorithm to extract the semantic structure of an existing web page and a page splitting scheme to partition the web page into smaller and logically related content blocks. Our approach enables a new mobile browsing experience by first presenting the thumbnail view of a give web page and then allowing the user to select a particular region to zoom in for detail information. Such a new browsing method overcomes the limitation of a mobile device with a small screen and makes them truly useful for information access. A large amount of experiment and performance evaluation was also conducted to show the effectiveness of our proposed algorithms.

7. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are thankful to Mingyu Wang, Xing Xie, and Zheng Zhang for many valuable discussions in shaping up this work.

8. RERERENCES

[1] Ashish, N. and Knoblock, C. Wrapper Generation for Semi-structured Internet Sources. Proc. PODS/SIGMOD’97, May 1997.

[2] Bickmore, T.W. and Schilit, B.N. Digestor: Device-independent Access to the World Wide Web. Proc. of the 6th WWW Conference, 1997, pp655-663.

[3] Buyukkokten, O., Garcia-Molina, H. and Paepcke, A. Accordion Summarization for End-Game Browsing on PDAs and Cellular Phones. Proc. of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2001, pp213-220.

[4] Buyukkokten, O., Garcia-Molina, H. and Paepcke, A. Seeing the Whole in Parts: Text Summarization for Web Browsing on Handheld Devices. Proc. of WWW-10, May 1-5, 2001, Hong Kong.

[5] Chen, J.L., Zhou, B.Y., Shi, J., Zhang, H.J. and Wu, Q.F. Function-based Object Model Towards Website Adaptation. Proc. of WWW-10, May 1-5, 2001, Hong Kong.

[6] Fox, A., Gribble, S.D., et al. Adapting to Network and Client Variation Using Infrastructural Proxies: Lessons and Perspectives. IEEE Personal Communication, V5, I4, 1998, pp10-19.

[7] Gu, X.D., Chen, J.L., Ma, W.Y., Chen, G.L. Visual Based Content Understanding towards Web Adaptation. 2nd Intl. Conf. on Adaptive Hypermedia and Adaptive Web Based Systems (Malaga, Spain, May 2002), pp164-173.

[8] Hammer, J., Garcia-Molina, H., Cho, J., Aranha, R. and Crespo, A. Extracting Semistructured Information from the Web. Proc. PODS/SIGMOD’97, May 1997.

[9] Hori, M., Kondoh, G., Ono, K., Hirose, S. and Singhal, S. Annotation-Based Web Content Transcoding. Proc. of WWW-9, Amsterdam, Holland, May 2000.

[10] Milic-Frayling, N. and Sommerer, R. SmartView: Flexible Viewing of Web Page Contents. Poster paper at the Eleventh World Wide Web Conference, Hawaii, 2002 (http://www2002.org/CDROM/poster/172/).

[11] Rahman, A.F.R., Alam, H., Hartono, R. and Ariyoshi, K. Automatic Summarization of Web Content to Smaller Display Devices. In: Post Presentations of 6th International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, Seattle, The United States, Sept. 10-13, 2001.

[12] W3C. Cascading Style Sheets. http://www.w3.org/Style/CSS/

[13] W3C. HTML 4.0 specification. http://www.w3.org/TR/html4/

[14] Wang, Y.L. and Hu, J.Y. A Machine Learning Based Approach for Table Detection on The Web. Proc. of WWW2002, May 7-11, 2002, Honolulu, Hawaii, USA.

[15] Yang, Y.D., Chen, J.L. and Zhang, H.J. Adaptive Delivery of HTML Contents. WWW9 Poster Proceedings, May, 2000, pp24-25.

[16] Yang, Y.D. and Zhang H.J. HTML Page Analysis Based on Visual Cues. In: 6th International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, Seattle, The United States, Sept. 10-13, 2001.