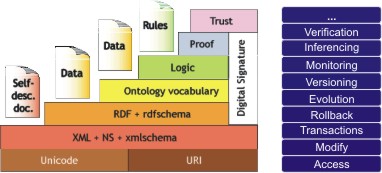

Static and dynamic aspects of the Semantic Web layer cake.

Ontologies are increasingly being applied in complex applications, e.g. for Knowledge Management, E-Commerce, eLearning, or information integration. In such systems ontologies serve various needs, like storage or exchange of data corresponding to an ontology, ontology-based reasoning or ontology-based navigation. Building a complex ontology-based system, one may not rely on a single software module to deliver all these different services. The developer of such a system would rather want to easily combine different -- preferably existing -- software modules. So far, however, such integration of ontology-based modules had to be done ad-hoc, generating an one-off endeavour, with little possibilities for re-use and future extensibility of individual modules or the overall system.

This paper is about an infrastructure that facilitates plug'n'play engineering of ontology-based modules and, thus, the development and maintenance of comprehensive ontology-based systems, an infrastructure which we call an Ontology Software Environment. The Ontology Software Environment facilitates re-use of existing ontology stores, editors, and inference engines. It provides the basic technical infrastructure to coordinate the information flow between such modules, to define dependencies, to broadcast events between different modules and to transform between ontology-based data formats.

Each application area, like E-Commerce or eLearning, uses its own, usually proprietary, ontology language and format. In the following we limit ourselves to the languages defined in the Semantic Web - an augmentation of the current WWW that adds machine understandable content to web resources by ontological descriptions. The ontology languages are currently becoming de jure standards specified by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) and thus will be of importance in the future.

The paper is structured as follows: First, we provide a brief overview about the Semantic Web in section 2 and motivate the need for an Ontology Software Environment via a common usage scenario in section 3. We derive requirements for such a system in section 4. Sections 5 and 6 describe the design decisions that we can derive from important requirements, namely extensibility and lookup. The conceptual architecture is then provided in section 7. section 8 presents the KAON SERVER, a particular Ontology Software Environment for the Semantic Web which has been implemented. Related work is discussed in section 9 before we conclude .

The Semantic Web augments the current WWW by adding machine understandable content to web resources. Such contents are called metadata whose semantics can be specified by making use of ontologies. Ontologies play a key-role in the Semantic Web as they provide consensual and formal conceptualizations of a particular domain, enabling knowledge sharing and reuse.

Figure 1 shows both the static and dynamic parts of the Semantic Web layers. On the static side, Unicode, the URI and namespaces (NS) syntax and XML are used as a basis. XML's role is limited to that of a syntax carrier for any kind of data exchange. XML Schema defines simple data types like string, date or integer.

The Resource Description Framework (RDF) may be used to make simple assertions about web resources or any other entity that can be named. A simple assertion is a statement that an entity has a property with a particular value, for example, that this paper has a title property with value "An extensible ontology software environment". RDF Schema extends RDF with the concepts of class and property hierarchies that enable the creation of simple ontologies.

The Ontology layer features OWL (Ontology Web Language) which is a family of richer ontology languages that intend to replace RDF Schema. The Logic, Proof and Trust layers aren't standardized yet.

The dynamic aspects apply to data across all layers. It is obvious that there have to be means for access and modification of Semantic Web data. Apparently, transactions and rollbacks of Semantic Web data operations should also be possible and meet the well-known ACID (atomicity, consistency, independence, durability) properties known from DBMS. Evolution and versioning of ontologies are also an important aspect, as domain formalizations usually have to cope with change [13]. Like in all distributed environments, monitoring of data operations is needed, in particular for confidential data. Finally, reasoning engines are to be applied for the deduction of implicit information as well as for semantic validation.

This Section motivates the needs for the cooperation and integration of different software modules by a scenario depicted in Figure 2. The reader may note that some real-world problems have been abstracted away for the sake of simplicity.

Imagine a simple genealogy application. Apparently, the domain description, viz. the ontology, will include concepts like Person and make a distinction between Male and Female. There are several relations between Persons, e.g. hasParent or hasSister. This domain description can be easily expressed with standard description logic ontologies. However, many important facts that could be inferred automatically have to be added explicitly. A rule-based system is needed to capture such facts automatically. Persons will have properties that require structured data types, such as dates of birth, which should be syntactically validated. Such an ontology could serve as the conceptual backbone for the information base of a genealogy portal. It would simplify the data maintenance and offer machine understandability. To implement the system, all the required modules, i.e. a rule-based inference engine, a DL reasoner, a XML Schema data type verifier, would have to be combined by the client applications themselves. While this is a doable effort, possibilities for re-use and future extensibility hardly exist.

The demands on an Ontology Software Environment from applications is to hook up to all the software modules and to offer management of data flow between them. This also involves propagation of updates and rollback behavior, if any module in the information chain breaks. In principle, an Ontology Software Environment responds to this need by bringing all the modules into one generic infrastructure. In the following Section, we will discuss requirements for this system.

Before we derive requirements from the scenario in section 3, we introduce the term of a Semantic Web Management System (SWMS), which is a particular type of Ontology Software Environment, especially designed for aiding the development of Semantic Web applications. Certain web communities may have dedicated Semantic Web Management Systems that feature all the software modules needed in that particular community. E.g., the bioinformatics community may have its ontologies hosted by a SWMS, accessible to all its portals and application developers.

Basically, the scenario establishes four groups of requirements. Clients may want to connect remotely to the SWMS and must be properly authorized. Hence, it is obvious that in a distributed system like the Semantic Web there is the need for connectivity and security.

On the other hand, a SWMS should respond to the static aspects of the Semantic Web layer cake. In particular it should offer support for all its languages. A desirable property is also to provide the ability to translate between the different languages, thereby increasing interoperability between existing software modules that mostly focus on one language only.

The dynamic aspects result in another group of requirements, viz. finding, accessing and storing of data, consistency, concurrency, durability and reasoning.

Finally, the system is expected to facilitate a plug'n'play infrastructure in order to be extensible. The last group of requirements therefore deals with flexible handling of modules. In the following paragraphs we will elaborate on the requirements in more detail.

In the following sections 5 to 7, we develop an architecture that is a result from the requirements put forward in this Section. After that we present the implementation details of our Semantic Web Management System called KAON SERVER.

Due to the requirement of extensibility, the Microkernel pattern is the fundamental paradigma of our design. The Microkernel pattern allows to adapt to changing system requirements. It separates a minimal functional core from extended functionality and application-specific parts. The Microkernel itself serves as a socket for plugging in these extensions and coordinates the collaboration of extensions [4].

In our setting, the Microkernel's minimal functionality must take the form of simple management operations, i.e. starting, ini tializing, monitoring, combining and stopping of software modules. This approach requires software modules to be uniform so that they can be treated equally by the kernel. Hence, in order to use the Microkernel, all extensions have to be brought into a certain form. We paraphrase this process as making existing software deployable, i.e. bringing existing software into the particular infrastructure of the Semantic Web Management System, that means wrapping it so that it can be operated by the Microkernel. In our terminology, a software module becomes a deployed component by this process.

Hence, we refer to the process of registering, possibly initializing and starting a component as deployment.

Apart from the cost of making existing software deployable, another drawback of this approach is that performance will suffer slightly in comparison to stand alone use, as a request has to pass through the kernel first (and possibly the network). A client that wants to make use of a deployed component's functionality talks to the Microkernel, which in turn passes requests on to the providers of functionality.

On the other hand, the Microkernel architecture offers several benefits. By making existing functionality, like RDF stores, inference engines etc., deployable, one is able to treat everything equally. As a result, we are able to deploy and undeploy components ad lib, reconfigure, monitor and possibly distribute them dynamically. Proxy components can be developed for software that cannot be made deployable for whatever reasons. Throughout the paper, we will show further advantages, among them

This Section presents our support for the requirement "lookup of software modules" stated in section 4. A client typically wants to find the components, which provides the functionality needed at hand. Therefore a dedicated component, called registry is required, which stores descriptions of all deployed components, and allows to query this information. Application developers can distinguish between several types of components:

Each component can have attributes like the interface it implements, its name, connection parameters as well as several other low-level properties. Besides, we can express associations between components, which can be put in action to support dependency management and event notification systems. This allows us to express that an ontology store component can rely on an RDF store for actual storage. The definitions above contained a taxonomy, e.g. it was stated that "functional component" is a specialization of "component" etc.

Thus, it is obvious to formalize taxonomy, attributes and associations in a management ontology as outlined in Figure 3 and Table 6. The ontology formally defines which attributes a certain component may possess and categorizes components into a taxonomy. Hence, it can be considered as conceptual agreement and consensual understanding of the management world between a client and the SWMS. In the end, concrete and specific functional components, for example KAON's RDF Server or the Engineering Server (cf. subsection 8.5) would be instantiations of corresponding concepts.

Attributes and associations of Component

| Concept | Property | Range |

| Component | Name | String |

| Interface | String | |

| ... | ... | |

| receivesEvent | Component | |

| sendsEvent | Component | |

| dependsOn | Component | |

| ... | ... |

The support to important requirements, viz. extensibility and lookup of software components establishes the basis for the architecture of the SWMS. The next Section gives a brief overview about the conceptual architecture of our implementation.

When a client first connects to the SWMS it will typically perform a lookup for some functional components it wants to interact with. The system will try to locate a deployed functional component in the registry that fulfills to the user query.

The lookup phase is followed by usage of the component. Here, the client can seamlessly work with the located functional component. Similar to CORBA, a surrogate for the functional component on the client side is responsible the communication over the network. The counterpart to that surrogate on the SWMS side is a connector component. It maps requests to the kernel's methods. All requests finally pass the management kernel which routes them to the actual functional component. In between, the properness of a request can be checked by security interceptors that may deal with authentication, authorization or auditing. Finally, the response passes the kernel again and finds its way to the client via the connector.

After this brief procedural overview, the following paragraphs will explain the architecture depicted in Figure 4. Note that in principle, there will be only three types of software entities: components, interceptors and the kernel.

A connector handles network communication with the system via some networking protocol. On the client side, surrogates for functional components are possible that relieve the application developer of the communication details. Besides having the option to connect locally, further connectors are possible to offer remote connection: e.g. via Java's Remote Method Invocation (RMI) protocol. Another example embodied in our implementation is a Web-frontend that renders the system interface into a HTML user interface and allows to interact with the system via the HTTP protocol.

The Microkernel described in section 5 is provided by the management kernel and deals with the discovery, allocation and loading of components, that are eventually able to execute a request. The registry hierarchically categorizes the descriptions of the components. It thus simplifies the lookup of a functional component for a client (cf. section 6). As the name suggests, dependency management allows to express and manage relations between components. Besides enforcing classical dependencies, e.g. that a component may not be undeployed if others still rely on it, this also offers a basis for implementing event listeners, which allow messaging as an additional form of inter-component communication.

Security is realized by several interceptors which guarantee that operations offered by functional components (including data update and query operations) in the SWMS are only available to appropriately authenticated and authorized clients. Each component can be registered along several interceptors which act in front and check incoming requests. Sharing generic functionality such as security, logging, or concurrency control lessens the work required to develop individual component implementations when realized via interceptors.

The software modules, e.g. XML processor, RDF store, ontology store etc., reside within the management kernel as functional components (cf. section 5). In combination with the registry, the kernel can start functional components dynamically on client requests. Table 7 shows how the requirements established in section 4 are supported by the architecture. Note that some requirements are eventually implemented by concrete functional components. Leaving those requirements aside in the conceptual architecture, e.g. language standards, increases the generality of the architecture, i.e. we could make almost any existing software deployable and use the system in any domain, not just in the Semantic Web. In the following Section we discuss a particular implementation, KAON SERVER, that realizes functional components specific for the Semantic Web.

Architectural support of requirements

| Requirement \ Design Element | Connectors | Kernel | Registry | Interceptors | Dependency Management | Functional Component |

| Connectivity | x | |||||

| Security | x | |||||

| Language Support | x | |||||

| Semantic Interoperability | x | |||||

| Ontology Mapping | x | |||||

| Ontology Storage | x | |||||

| Consistency | x | |||||

| Concurrency | x | x | ||||

| Durability | x | |||||

| Reasoning | x | |||||

| Extensibility | x | |||||

| Lookup | x | |||||

| Dependencies | x |

Our Karlsruhe Ontology and Semantic Web Tool suite (KAON, cf. http://kaon.semanticweb.org) provides a multitude of software modules especially designed for the Semantic Web. Among them are a persistent RDF store, an ontology store which is both optimized for concurrent engineering and direct access, ontology editors and many more. The tool suite relies on Java and open technologies throughout the implementation. KAON is a joint effort by the Institute AIFB, University of Karlsruhe as well as the Research Center for Information Technologies (FZI). KAON is a result of the efforts of several EU-funded research projects and implements requirements imposed by industry projects.

This Section presents the KAON SERVER which brings all those so far disjoint software modules plus optionally third party modules in a uniform infrastructure. KAON SERVER can thus be considered as a particular type of Semantic Web Management System optimized for and part of the KAON Tool suite. It follows the conceptual architecture presented in section 7. The development of the KAON SERVER is carried out in the context of the EU IST funded WonderWeb where it serves as main organizational unit and infrastructure kernel.

In the case of the KAON SERVER, we use the Java Management Extensions (JMX) as it is an open standard and currently the state-of-the-art for component management.

Java Management Extensions represent a universal, open technology for management and monitoring. Basically, JMX defines interfaces of managed beans, or MBeans for short, which are Java objects that represent JMX manageable resources. MBeans conceptually follow the JavaBeans components model, thus providing a direct mapping between JavaBeans components and manageability. MBeans are hosted by an MBeanServer which provides the services allowing their manipulation. All management operations performed on the MBeans are done through interfaces on the MBeanServer. Thus, in our setting, the MBeanServer realizes the Microkernel and components are realized by MBeans.

Apart from the interceptors, all functionality takes the form of MBeans, be it a software module which a client wants to use or functionality that realizes SWMS logic like a connector, for instance. In other words, the MBeanServer is not aware of those differences. For a Semantic Web Management System such as KAON SERVER it is therefore important to make the difference explicit in the registry.

Each MBean can be registered with an invoker and a stack of interceptors that the request is passed through. The invoker object is responsible for managing the interceptors and sending the requests down the chain of interceptors towards the actual MBean. For example, a logging interceptor could be inserted to implement auditing of operation requests. A security interceptor could be put in place to check that the requesting client has sufficient access rights for the MBean or one of its attributes or operations. The invoker itself may additionally support the component lifecycle by controlling the entrance to the interceptor stack. When a component is being restarted, an invoker could block and queue incoming requests until the component is once again available (or the received requests time out), or redirect the incoming requests to another component that is able to service the request.

We realized the registry as MBean and re-used one of the KAON modules which have all been made deployable (cf. subsection 8.5). The main-memory implementation of the KAON API holds the management ontology. When a component is deployed, its description (usually stored in an XML file) is properly placed in the ontology. A client can use the KAON API's query methods to lookup the component it is in need of.

Dependency Management is another MBean that manages relations between any other MBeans. An example would be the registration of an event listener between two MBeans.

The functionality described so far, i.e. the JMX Microkernel, the interceptors, the registry and the dependency management could be used in any domain not just the Semantic Web. In the remaining subsections we want to highlight the specialties which make the KAON SERVER suited for the Semantic Web.

First, there is our KAON Tool suite which has been made deployable. Furthermore, we envision a functional component that enables semantic interoperability of Semantic Web ontologies as well as an ontology repository. Several external services (inference engines in particular) are also deployable, as we have developed proxy components for them. All of them are discussed in the following subsections and, besides the KAON tools, can be considered as outlook.

Two Semantic Web Data APIs for updates and queries are defined in the KAON framework - an RDF API and an ontological interface called KAON API. An OWL interface will follow in the future. The different tools implement those APIs in different ways like depicted in Figure 5 and will become functional components. They are discussed in subsection 8.6.

The RDF API consists of interfaces for the transactional manipulation of RDF models with the possibility of modularization, a streaming-mode RDF parser and an RDF serializer for writing RDF models. The API features the object oriented pendants to the entities defined in [7] as interfaces. A so-called RDF model consists of a set of statements. In turn, each statement is represented as a triple (subject, predicate, object) with the elements either being resources or literals. The corresponding interfaces feature methods for querying and updating those entities, respectively.

Our ontological API, also known as KAON API, currently realizes the ontology language described in [9]. We have integrated means for ontology evolution and a transaction mechanism. The interfaces offer access to KAON ontologies and contain classes such as Concept, Property and Instance. The API decouples the ontology user from actual ontology persistence mechanisms. There are different implementations for accessing RDF-based ontologies accessible through the RDF API or ontologies stored in relational databases using the Engineering Server (cf. Figure 5).

This implementation of the RDF API is primarily useful for accessing in-memory RDF models. That means, an RDF model is loaded into memory from an XML serialization on startup. After that, statements can be added, changed and deleted, all encapsulated in a transaction if preferred. Finally, the in-memory RDF model has to be serialized again.

The RDF Server is an implementation of the RDF API that enables persistent storage and management of RDF models. This solution relies on a physical structure that corresponds to the RDF model. Data is represented using four tables, one represents models and the other one represents statements contained in the model. The RDF Server uses a relational DBMS and relies on the JBoss Application Server that handles the communication between client and DBMS.

As depicted in Figure 5, implementations of the ontological KAON API may use implementations of the RDF API.

A separate implementation of the KAON API can be used for ontology engineering. This implementation provides efficient implementation of operations that are common during ontology engineering, such as concept adding and removal by applying transactions. A storage structure that is based on storing information on a metamodel level is applied here. A fixed set of relations is used, which corresponds to the structure of the used ontology language. Then individual concepts and properties are represented via tuples in the appropriate relation created for the respective meta-model element. This structure was not chosen before by any other RDF database, however it appears to be ideal for ontology engineering, where the number of instances (all represented in one table) is rather small, but the number of classes and properties dominate. Here, creation and deletion of classes and properties can be realized within transactional boundaries.

One optional component we envision is a Ontology Repository, allowing access and reuse of ontologies that are used throughout the Semantic Web, such as WordNet for example. Within the Wonderweb project several of them have been developed [11].

In the more distant future we plan to include a component that allows Semantic Interoperability between different types of ontology languages as a response to the requirement put forward in section 4. In the introduction, we already mentioned RDFS, OWL Lite, OWL DL and OWL Full. Besides, there are older formats, like DAML+OIL and also proprietary ones like KAON ontologies [9]. This component should allow the loading of KAON ontologies in other editors, like OILEd [2], for instance. It is clear that such an ontology transformation is a costly task, i.e. information will probably be lost as the semantic expressiveness of the respective ontology languages differ.

The definitions in section 6 already clarified that external services live outside the KAON SERVER. So-called proxy components have to be developed that are deployed and take care of the communication. Thus, from a client perspective, an external service cannot be distinguished from an actual functional component. At the moment we are adapting several inference engines: Sesame [6], Ontobroker [12] as well as a proxy component for description logic classifiers that conform to the DIG interface, like FaCT [5].

We consider two distinct topic areas as related work. One topic area is the work done for RDF data management systems. The other is middleware.

All of the following data management systems focus on RDF language only. Hence, they are not build with the aspect of extensibility in mind and provide more specialized components than our implementation does. Hence, they offer more extensive functionality wrt. RDF.

Sesame [6] is a scalable, modular, architecture for persistent storage and querying of RDF and RDF Schema.Sesame supports two query languages (RQL and RDQL), and can use main memory or PostgreSQL, MySQL and Oracle 9i databases for storage. The Sesame system has been successfully deployed as a functional component for RDF support in KAON SERVER.

RDFSuite [1] is a suite of tools for RDF management provided by the ICS-Forth institute, Greece. Among those tools is RDF Schema specific Database (RSSDB) that allows to query RDF using the RQL query language. The implementation of the system exploits the PostgreSQL object-relational DBMS. It uses a storage scheme that has been optimized for querying instances of RDFS-based ontologies. The database content itself can only be updated in a batch manner (dropping a database and uploading a file), hence it cannot cope with transactional updates, such as the KAON RDF SERVER.

Developed by the Hewlett-Packard Research, UK, Jena [8] is a collection of Semantic Web tools including a persistent storage component, a RDF query language (RDQL) and a DAML+OIL API. For persistence, the Berkley DB embedded database or any JDBC-compliant database may be used. Jena abstracts from storage in a similar way as the KAON APIs. However, no transactional updating facilities are provided.

Much research on middleware recently circles around so-called service oriented architectures (SOA), which are similar to our architecture, since functionality is broken into components - so-called Web Services - and their localization is realized via a centralized replicating registry (UDDI). However, here all components are stand-alone processes and are not manageable by a centralized kernel. The statements for SOAs also holds for previously proposed distributed object architectures with registries such as CORBA Trading Services [3] or JINI.

Several of today's application servers share our design of constructing a server instance via separately manageable components, e.g. the HP-AS or JBoss. However, they do not allow to manage the relations between components and their dependencies, as well as dynamic instantiation of deployed components due to client requests - rather all components have to be started explicitly via configuration files or a management interface.

We have presented the requirements for an Ontology Software Environment and the design of a Semantic Web Management System. Our prototype implementation - the KAON SERVER - has already illustrated its utility in the WonderWeb project. Individual components of the system are successfully used within the several other projects both in academia and industry.

In the future, we will address two research aspects: First, we envision to incorporate information quality criteria into the registry. Users will then be able to query information based on criteria like "fitness for use", "meets information consumers needs", or "previous user satisfaction" [10]. We will also support aggregated quality values, which can be composed of multiple criteria. Second, we plan to implement dedicated components that allow to inter-operate between different Semantic Web languages. For example, a dedicated component may be able to explicate all implicit facts in an ontology base for RDF clients.