|

Latest Version

|

The Internet community is currently focused on the subject of "Web services". Though there is considerable deliberation as to the exact meaning of this term, and consequently to the true level of innovation it implies, sic. "Isn't this what we have been doing all along?" , there is consensus on a quartet of tools ( XML, SOAP , WSDL and UDDI ), general agreement on the need for wide scale interoperability, and a fledging optimism that Web services can release the commercial potential of the Web.

Though for many, the deployment of Web services is a rather strait laced affair; fixing things around the office, gluing together applications and resources from reluctant and disjointed operating systems and platforms, letting J2EE productions talk to .NET productions and so forth, one also senses a vision of evolutionary process, a Dawkins - Loewenstein inspired belief that information itself is evolving, becoming more powerful. The key word here is discovery; electronic agents traversing across universal resource directories, discovering new resources and doing what humans can't - making a huge amount of decisions in a very short span of time. It is expected that the resources pointed out by the directory-agent interaction will be ever online, automated, specialized and effective and that our agents will negotiate with these resources, lambently buying, selling, and trading .

This paper explores the eventual consequences of a universally accessible Web Service directory, not as a new paradigm for accessing online applications, but rather as a fundamental element of public infostructure, that is, as a directory of cultural, recreational, educational, and commercial resources, endeavours and ideas that might be considered as of value to society comparable to public roads, hospitals and schools; Web services as repositories of knowledge, Web services as harbingers of culture, Web services as tools of learning and entry points to societal participation.

Taking a cinemascope perspective, we can say that any representation of information in plural is essentially a directory and any access provided to the directory, a directory service. The term Directory Services comes with a rather narrow definition in our ITC community - more or less the administration of rights and privileges in networks, but in this paper we are concerned with the everyday concept of a directory as information in plural and any application providing or improving access to that directory as directory services.

So through out the text, we will exercise considerable breadth as to what we call a directory. Obviously the current UDDI specification was not designed with this sort of thing in mind, but it is perhaps in keeping with the vision of Web services as reaching beyond the known and adjacent world to the unknown and possible world, where hardwiring and business-as-usual are replaced by exploration and discovery.

How will we navigate this? Initial contact with the unknown must be through some sort of index or directory that we or our agents can relate to. When looking for information in an encyclopaedia, we approach it first as an index. Then, once we have found a desired article it becomes a knowledge source. But within that knowledge source a new directory unfolds as we learn about the subject at hand, pointing outwards towards related knowledge sources.

Traditionally a directory is a gathering point for descriptions about objects or resources. Each description is a proxy or designator for one or more resources. The resources may or may not exist in the directory. The directory (in most cases) points to external resources, perhaps through contact information such as an address and telephone number, requiring subsequent actions of a user, or perhaps through a hyperlink, where the user is hardly aware of the address she has been taken to. On the other hand, dictionaries and encyclopaedias are "self containing" directories with their own internalized resources.

In this paper we will first look at directory design issues, then directory business models and finally postulate as to the role of one particular directory as a key element in building public infostructure.

The design of directories shares the considerations common to all OIEs (Orderly Information Environments). Compare, for example, the traditional components of quality in the field of statistics below to the list of directory issues that follows them.

Resource descriptions are gathered in a particular directory based upon some aspect of commonality, referred to in this text as proximities . Proximities can be calculated in geographical or geopolitical distance such as the incorporated area of a township or state. Proximities can be measured in the relevance of common resource attributes like; all TV programs having a channel and a viewing time, or all the available medicines, as classified by the diseases they are intended to remedy.

The attributes of language, demographics, asset specificity, use-specificity etc. can all be represented as proximities and therein as qualifiers for sorting entries and optimizing directory publishing.

In a relational database, resources sharing attribute commonalities are arranged in tables, with attributes in columns and resource designators in rows. As one can easily see, this works best the greater the sharing of attributes. If there are disparate types of resources to be published, (say) movies being shown and shoes being sold, then a directory architect, being hard pressed to find columns of common attributes for shoes and movies, might just decide that it was better to create a separate directory for each domain. When to share directory space and when to build separate abodes, is a typical design challenge for info-system builders.

Directories are built to be reused. They are structured for efficient access and upkeep. The commonality of attributes makes for easy comparisons and conditional queries such as "find me all the shoes that are blue and suede". The convenience of attribute commonality can serve to encourage the rounding off of properties. Maybe some shoes are more blue than others and maybe some shoes are really galoshes or slippers. A directory designer tends to round off when possible since precision has its costs. This makes for simpler queries but might negatively effect the quality of the resource description.

Directories are reproduced in some form of media, such as paperbacked catalogues or CD-ROMs, and the physical properties of media have always influenced the contents of the directory. Telephone catalogues are always trade-offs between size and weight on the one hand and the probability of look-ups on the other. Knowing that most look-ups are local, the publishers of telephone directories try to optimize publishing and distribution costs through the segmenting of geopolitical areas. We assume that digital network publishing radically changes the traditional equations here, but since most of the directories on the Internet today are ports from a previous media, they often inherit the constraining factors of their previous existence rather than exploit the advantages of the new..

Much directory information is subject to constant change. Each publisher has to decide on a trade-off point between being up-to-date and the cost of publishing new editions. Though online directory publishing is seen as an eliminator of this problem, this is not entirely the case. When a new edition is published, such as for a catalogue of medicines, the edition signals simultaneously the invalidity of previous issues. This alerts users to the possibility that an earlier listing is no longer up-to-date, perhaps even containing erroneous information. Piecemeal, real-time updates must choose between signalling for every update, which could be a great nuisance, or causing directory users to be dependent upon continuous look-ups just to make sure a listing had not changed.

Furthermore, in online publishing the temptation to dynamically update content can create severe problems of versioning and time axis compatibility.

The utilitarian effect on directories seems rather obvious. But the commonalities of use do not always parallel the commonalities of resource description. A builder might have to look in several different directories to find tools and materials that are part of the same work process. But in general usage commonalities are important. A newspaper puts ads for movies and nightlife in the same section. You expect to find recipes for edible dishes in a recipe book, despite the diverse nature of ingredients and utensils specified.

If you were looking for all the used cars up for sale within a 30 kilometre radius from your home, would you be interested in a directory that contained all the cars or just some of them? Well that depends. You might welcome a directory that exercised pre-selection and represented just a sampling of all the cars - if the total amount of cars in the area were just too overwhelming to choose from. But if the makeup of that pre-selection should observe certain irrational criteria, for example only cars to the south of you, or only cars with an even number of kilometres on their speedometer, or only cars whose owners names started with "S", then that night not be so appealing.

We humans can only deal effectively with so many alternatives is a selection process and we are willing to accept pre-selection filtering, but we know full well that some filtering modules work more to our interest than others. The nature of pre-selection filtering is often the results of a business model as described further on in the text.

The funnel in figure 3. illustrates a clogged pre-selection process. There is backlog of alternatives that will never make it through to final selection. Which alternatives that make it in to the funnel depends on the particular business model in place. Perhaps it comes as no surprise that a common if irrational pre-selection process is simply alphabetical ordering resulting in higher success rates for just out about and service or person whose name comes early in the alphabet.

Quality is of course essential to any OIE, but there is a potential conflict between statements 6 and 7. Completeness in a directory is not necessarily synonymous with quality. Without a correspondingly effective pre-selection process, completeness can lead to uselessness. The type of pre-selection process and consequently the nature of the directory is determined by the "business model" behind the directory.

Before we look at business models, lets see how Metcalfe's law relates to directories. Robert Metcalfe the inventor of Ethernet, has said (roughly) that the value of a network is equal to the square of the number of its members. One should balance this "value" with some sort of utility coefficient - since the value of a network, where all the nodes are uninterested in talking to each other, is only a potential value that might never be realized.. But if we take a granular or layered approach to networks we can see how nodes at selected use-layers do collectively add value.

This is part of the magic of the Internet, where so many varied activities can take place simultaneously in some particular use-layer. Puts and calls on stock issues cross paths with teenage chat, films and control codes determining the blade angles of remote windmills. So even if we have no desire to talk to each other, by sharing the basic infrastructure, we are exploiting one great commonality and fulfilling Metcalfe's law.

For any network, be it electronic or horse driven, there are discrete layers where resource sharing influences the cost of usage. Traders might join together in camel caravans and spend months together crossing a inhospitable dessert, only to set up fiercely competitive stalls once they reach Samarqand. Today we can find such layers or strata in transport, packaging, storage, delivery, lobbying, outsourcing and so on . The list seems endless as long as points of demarcation can be established separating those tasks that are shared from those that are not. What is important is that technology constantly effects any calculation on the benefits of load sharing for each tier or level in the food chain.

In a general sense, this is what makes technology a disruptive force for businesses. Since all businesses are themselves a multi-tiered balancing act between the exploitation of commonalities and exclusivities, technological advancements not only enable a company to improve production, administration and distribution, they also upset ingrained balancing strategies in ways that might be not be understood by owners and managers.

Since directory processes can be layered or modularized just like networks, the choice of whether to exploit exclusivities or commonalities can be made individually for each module. For example a directory service could be divided up into 4 modular layers, based on acquisition - storage - distribution and dissemination. Different commonality-exclusivity ratios can exist for each module. Advertising for example almost always exploits commonalities, ads exist on the same TV programs and in the same magazines, while some firms would not considering sharing an ad agency with a competitor.

Many believe the natural evolution of the directory to be towards becoming transactional. That is not only describing resources, but brokering them (at a fee). For this reason directory ownership and monopolization can be seen as the ultimate land grab; the revenge of the middleman in era where middlemen were supposed to disappear. For now though, we will be only concerned with the function of a directory as a representational proxy and look at some typical business models as demonstrated with symbolic use cases.

We will call the directory user Alice, the infomediary maintaining the directory Dave, and the owner of a resource being listed Carol. There is also a fourth party named Bob, who has his own reasons as to why Alice should have access to Carol's resources.

The seven arrows in the diagram do not illustrate the flow of information but rather the flow of cash between participants. There are 127 possible cash flow variations and no doubt each one of them is in operation somewhere in the world, but that is irrelevant for our present purposes. The important aspect is that each cash flow conduit when turned on or off - directly influences the nature and quality of the directory.

Some simplified models (before Bob gets involved) are:

While these models might not necessarily occur as pure-plays, each cash flow conduit directly relates to the quality and nature of information disseminated.. In the radio model for example, Carol pays Dave for the quality of his distribution. Alice may rightly be sceptical about the value of the information in this model since she receives it for free and therefore can place no demands on Dave.

In a pure-play Michelin Guide model (number 2), it is Carol who can make no demands on Dave, excepting hopefully his impartiality, but Alice does, since she is paying for, not only the listings, but his esteemed opinion as well. It is considered important that Carol does not pay Dave, as this could potentially influence the quality of his opinion, but there are work-arounds for Dave on this dilemma as explained further on.

In Model number three, the newspaper model, Dave hopes to get income from both Alice and Carol, making him responsible to both. Dave is often expected to exercise editorial impartiality in matters concerning Carol and her competitors. Yet to generate income, Dave can offer Carol variable levels of visibility at a price. Though the newspaper model is quite common and considered to be a juicy middleman position, Dave runs the risk of competing with those models which offer free services to Alice or Carol. since there is no marginal increase in cost for Alice and Carol to publish in parallel on hose free services. If one of those models takes off Dave is in Trouble.

The timesharing model has a sleazy connotation for many of us. We all share a natural suspicion of people paying us to look at things we might eventually feel obligated to buy against our better judgement. But many see this as a model of the future as Alice becomes more powerful at Carol's expense. It is assumed that modern communication technology makes it easier to exploit the commonality of consumership

The cable TV model does not specify how Dave recoups the money he pays Carol. Of course Alice has to pay Dave, but perhaps not in direct proportion for what he has bought from Carol. Carols product might be passed on to Alice for free so that Dave might induce Alice to purchase something else. Often when a bouquet of products and services is bundled, individual price tickets are kept opaque by the seller.

In any model where Dave is expected to act impartially in the interest of completeness, yet at the same time offer showcasing (increased exposure) if Carol is prepared to pay for it, there exists an potential conflict of interest. The normal procedure is to demarcate between editorial responsibility and paid-for copy with the help of an "ad-flag"; some sort of visible border that indicates the boundaries between fact and contention. On the search engine Google, such demarcation is accomplished by labelling paid-for exposure with 'sponsored link' tags.

In the yellow page type of telephone directory, where completeness with impartiality, and showcasing are offered in parallel, any business with a telephone subscription is included for free, yet at the same time a business can increase their visibility at an extra cost. The ad-flag in such a directory is essentially any listing that distinguishes itself from the pack, from bold text to full page ads, and Alice is expected to recognize this distinction though it can at times be quite obscure.

One might argue that Carol's willingness to increase her visibility through showcasing is perhaps in no way indicative of the suitability of her services for the benefit of Alice. One might argue that Alice would more wisely spend her money to keep Dave impartial and let him or some other trusted part make qualified judgements as to whether Carol's or her competitor's services were those best suited to Alice's needs. But in the real world Carol's ability to successfully showcase is also an indication of her strengths and durability and in the long term this can be of value to Alice in her decisions about potential trading partners.

So who is Bob and what does he have to do with Alice, Dave and Carol?

Bob is an entity with an interest in the directory which is separate from the other participants. Normally Bob is a collective force. Bob could be an elected authority representing the combined political will of Alice, Dave and Carol who sees the directory as an Infostructure - a resource for the good of society as a whole. Bob might think that the directory is an investment in better health or higher educational standards or merely a necessity to keep track of all the automobiles and houses in the land. Bob might see the directory as a stimulus to commerce and a subsequently larger tax base.

Bob might also be a collective force working solely on behalf of Carol. In many instances Carol will see advantages in joining together with her competitors in order to more effectively engage Alice or perhaps to put pressure on Dave. Bob might also be a collective force working on behalf of Alice and her fellow citizens, keeping tabs on both Dave and Carol.

In any event Bob, when representing collective interest sometimes works at cross purposes with the interests of individuals members of the collective.

Bob's actions can create economies of scale that are of benefit to the collective. In modern societies, Bob can be quite active promoting politically mandated general welfare. Of course today this is not necessarily carried out through the support of universal directory services. On the contrary, subvention of commerce, culture, education, physical fitness and health has usually taken the form of piecemeal intervention - that is, financial support for select individuals, institutions and activities. The concept; that through the promotion of universal directory services, benevolent administrators can create infostructure for the good of all, is not widespread. But then again the technology needed to do so has not previously been available.

To push a point provocatively, one could say that advertising is capitalism and directories are communism. In a directory, the uniformity of listings runs contrary to the relative power and magnitude of what they represent. In the Stockholm telephone catalogue one can find a large Fortune 500 concern, Johnson & Johnson Corporation right next to Johnson & Johnson Car Service, which is assumedly a significantly smaller enterprise. Both have telephone numbers, addresses and post numbers printed in the same 8 point font.

Entities that enjoy superior market share or brand recognition, called here POP, (Power of Presence) will normally strive to ensure that their POP is maintained in all possible arenas. This is true, not only for firms, but also for organizations and individuals. In case any one hasn't noticed, the ordering and size of a cast of names on a cinema poster or marquee is not a trivial affair. Microsoft has a larger booth than the Acme Software Company at Comdex or CeBit and manufacturers pay dearly to get their products appropriately showcased in stores. Just recently Levi Strauss won a EU court battle to ensure that their jeans would remain more expensive than that of the competition as they feel their POP demands such a distinction.

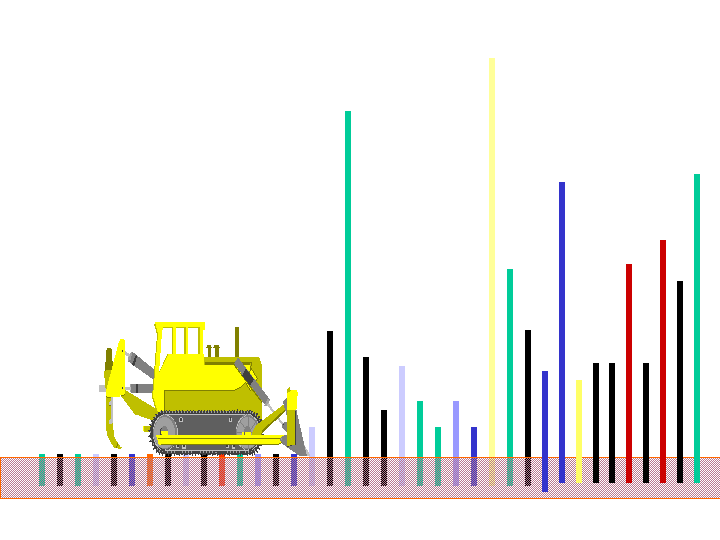

In the figure below, each vertical line represents Power of Presence. Ex. the difference between "Coca-Cola" and "Jolly-Cola", or "Madonna" and "Jane Doe". Keep in mind that POP is often geopolitically relative, so that in Canada the strength of FC Barcelona (a football club enjoying huge POP in Europe) might be greatly reduced, ditto for Billy Graham Jr. in Pakistan.

There is a shaded area at the bottom of figure 7. We call this the threshold of visibility. The theory behind this threshold is that for every media type there exists a cut-off point where POP becomes so weak that whatever resource it represents literally disappear from view. The threshold of visibility can be very high in mass media channels and there is an explanation for that.

If we look at mass media as the trinity of

a paradox unfolds. The Infomediary is looking for economy of scale for her media product. She is looking to maximize profits by exploiting commonalities of interest through her distribution strategy. In traditional mass media broadcasting, such as magazines, newspapers, radio and television, distribution strategies are coupled to proximities. When we use the term broadcasting here, we mean a media form who's payload costs more to deliver the further it extends from the point of propagation. A newspaper is cheaper to deliver the shorter the distance its delivery trucks must travel. The cost of increasing the power of a radio transmitter becomes exponentially higher in relation to the resulting expansion in radius.

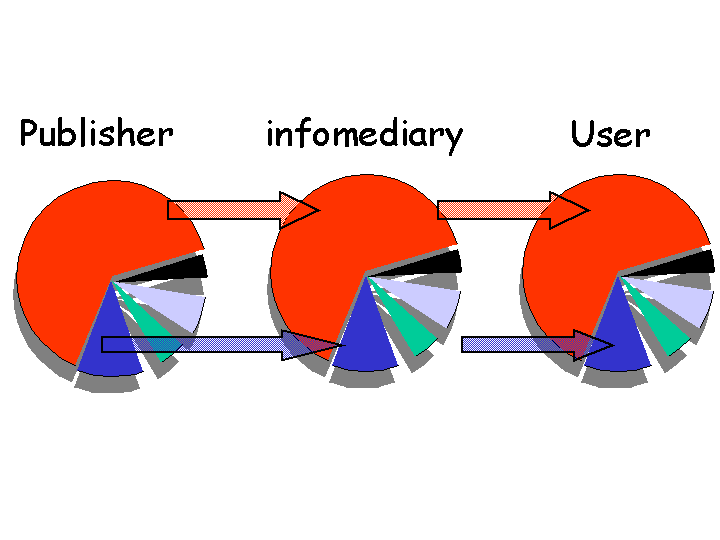

So Infomediaries will identify proximity concentrations and focus their distribution accordingly. For traditional mainstream media this usually means a proximity mix of distance and general interest. In the diagram below the various pie slices represent common interests. The Infomediary will know or assume general interest profiles for her average consumer. Though each individual consumer obviously has diversified interests that vary from the generalized profiles assumed by the Infomediary, the costs of addressing these interests will be disproportionate to the income generated.

This causes Infomediaries to sustain the status quo of POP levels. Consumers interests are satisfied in relation to their conformance to the fictive generalized consumer profile. This system works to the disadvantage of non-conformance and individualized interests. Studies of cable television networks in the USA have shown that despite the profusion of media space, narrow interest channels are constantly pushed aside by broad interest channels.

This does not imply that mainstream broad interest publishing is always the most lucrative. On the contrary narrow interest audiences, particularly those with deep pocket purchasing power like doctors, create great revenues for those publishers that can pinpoint them. But pinpointing is not the same thing as broadcasting and technology is also changing the balance between them.

That is a difficult question, since the establishment of new technology is an ongoing process, and we are always aware of the next best thing long before it arrives. We are apt to say the Internet has changed this and the Internet has changed that, when we sometimes mean the Internet should or could. On many counts paper based media is still far superior to digital display based media. We can all pick up a flyer from our local food store right out of our mailboxes and immediately read it. And there is a good chance that we still will find a telephone number quicker in a paper based catalogue than through accessing a web page. Furthermore only a small minority of the worlds population has direct access to the Internet.

A major technical issue for universal directory ambitions is whether the economies of scale offered by the Internet are sufficient to offset the costs of maintaining the conditions of relevance, accuracy, timeliness and regularity, clarity and accessibility, comparability, coherence and completeness in very large orderly information environments. Furthermore as Economedis and others have pointed out. Networks may not reach their optimal size if network owners can not internalize on externalities. In plain language this means that if the exploitation of commonalities can not be financially realized and cashed in through some sort of collective system of profit and loss, there might not be incentives for network expansion.

The Internet in its current state is not a broadcast medium. The cost of distance is for all intents and purposes totally discounted. This is the basis of some Web service prophesies. If distances in fibre cable were taxed per kilometre the Internet would become a broadcast medium and many a vision, including those of this paper, could fall flat on their face. Since the current state of affairs is just as much the results of a technological accident as a technological innovation, we do well to remind ourselves that the Death of Distance is not a fact of life.

Three years ago, representatives from the Swedish national organizations for the promotion of culture, tourism, community services, adult- and primary education and sports met in Stockholm to discuss the possibilities for universal directory services for their combined sectors.

The goal of the meeting was to investigate how a universal directory could exploit the commonalities of each sector's information publishing needs, yet at the same time provide for each sector's exclusivities. A working group (The SkiCal Consortium) was formed to design and propose such a directory. The imagined user of this service was defined as a TimeSpender . From a Time Spender's point of view; a meeting of the city council, a Division 3 soccer game, going to a movie, or keeping a doctor's appointment are all similar - in the sense that the TimeSpender must make a commitment of her time and perhaps physically go somewhere. Tourists and locals citizenry are both TimeSpenders looking for optimal use of the resources in a particular area, and many local resources are as opaque for locals as they are for tourists..

In subsequent meetings a directory model was defined based on the queries of a TimeSpender, which was a departure from previous designs based on the needs of resource publishers. Of course both must be provided for, but at the time SkiCal work began there were a great deal of online services that seemingly only reflected the needs of the people running them. A list of queries that a TimeSpender might make in order to optimally interact with resources was eventually formalized in the SkiCal model.

In brief, these queries were sorted under the six interrogatives dubbed the Wha's.

SkiCal gave us the semantic structure to build a universal directory of resource access - a necessity in order to go further, but the hard part still remained. In essence the SkiCal working group was looking for an effect, as demonstrated in the figure below. The idea was to depreciate the traditional process of piecemeal subventions whose intention is to raise the POP level of individual resources and instead concentrate on lowering the threshold of visibility for the entire sector, or in this case a plurality of sectors.

Once the threshold of visibility is lowered so that even resources with minimal POP are exposed, harvesters can sweep the field uninfluenced by relative POP strengths. Of course the pitfalls of such a concept is that it discounts POP for those who already enjoy it and who possibly acquired it through considerable cost and effort.

It is known that the Internet's propensity for neutralizing POP dissuaded many brand name participants from spending advertising money. And any universal solution that discounts POP is risking mass absenteeism from those that have it. On the other hand, once (and if) a directory service surpasses a critical use level viz. a POP of its own, it could become inopportune for high level POP players to abstain.

The SkiCal Consortium was launched in the gold rush days of the internet, when anybody and his aunt could set up shop as a "Portal" for information in the sectors we were addressing. The most common portal model was what we refer to as a Tom Sawyer, named so after that Mark Twain character's remarkable ability to get other people to do his work

Tom Sawyer portals asked various businesses to come and paint their walls with information that could attract visitors. Several of the directory business models described above were practised, but a new model, were nobody paid nobody was often the results - which of course contributed to the demise of these sites.

Besides the problems with the nobody-pays-nobody model, it was readily apparent that for every site that came into existence, rather than enriching the network in a Metcalfian sense, they served to weaken it.

The reason for this was that the profusion of portals fragmented the market. Instead of plurality in resources offered, we were getting a plurality in portals offering them. The effect was to confuse TimeSpenders or at least make searching for resources a more complicated and time consuming affair. Nor were things being made easier for resource publishers who were being asked to paint many walls, sometimes paying for the pleasure.

One alternative to this problem is glaringly obvious - reduce the amount of portals. Reduce them all down to one. If a TimeSpender is assured that there is one directory with true completeness and quality, they will be more likely to use it and resource providers will have a much easier task publishing. In many real world situations the advantages of a one directory solution leads to an acceptable monopoly. This is true for telephone catalogues, TV guides and most poignantly the Internet DNS.

Instinctively we recoil from this type of solution and for good reason. Such a monopoly could stifle innovation in resource publishing and eventually lead to greater costs for publishers and users. And, one must ask themselves, by what criteria and authority might we decide just who should be entrusted with such a monopoly?

But The Internet itself is one directory. There is only one Internet, even if that just happens to be an historical (or evolutionary) accident. Much of the interest in Web services has to do with this oneness. The Internet is not considered a monopoly because that would imply singular ownership or control, and as we like to keep telling ourselves, nobody owns or controls the Internet. The Internet is not considered a directory, because we do not recognize it as an orderly information environment. OIEs, when they exist, do so as walled gardens approachable via the Internet, but not actually on it. The relative completeness of the Internet is seen as detrimental to quality since pre-selection processes appear to be either totally irrational or strategically rigged.

If the the internet is not a monopoly, than let us say it is a panopoly . Let us define "panopoly" as the ownership by many of a singular resource. A panopoly is driven by the desire to effectively exploit a shared commonality in order (somewhere down the line) to benefit the individual purposes of its members. And just as the Internet constitutes one very large panopoly, so may groups of lesser size create panopolies of their own within its network.

The SkiCal consortium came to accept that it was not its task to build another portal or directory over the resources of its member's domains, but rather to make better use of the universal directory already in existence - the Internet. The agreed strategy for doing this, was to strengthen the panopoly of resource publishers and promote the use of semantic structuring by all its members, subsidizing tools for SkiCal compliant resource publishing, lobbying for more government support, and publicizing the advantages of SkiCal. It is assumed that as the panopoly grows eventually a critical mass of SkiCal compliant information will tempt search engines to build customized modules for resource searches, similar to image search modules or specific language search modules.

This approach, which many find curiously ambitious, has up to now proved to be more viable than competing strategies, many of which have capsized in the dotcom deluge. SkiCal is, by Internet time metrics, a uniquely long term project and we will not know before some years have passed just how successful it might become. Much of the work so far as been done on a shoestring budget and not before the end of 2002 is it expected that, for example, all the tourist bureaux in Sweden will be SkiCal complaint.

The following rather pompous definition of Universal Synchronization points out an aspect of SkiCal that has always been tough to sell.

| Definition: Universal Synchronization Any resource or directory of resources, where temporal-spatial considerations are of significance for the resource, or to the human or electronic agent seeking to know about or utilize the resource, will publish, in a machine-readable format, the temporal-spatial coordinates of that resource. Any person or person's electronic agent wishing to know about, use, or negotiate the use of a resource will have the option of declaring in a machine-readable format any of her own temporal-spatial coordinates that might serve to optimize possible transactions. Any person or person's electronic agent wishing to interact with any other person or their electronic agent may optimize that interaction through publishing, in a machine-readable format, the temporal-spatial coordinates that might add value to that interaction. |

What is being expressed here is the fact that the opening times and operating

hours of businesses and services are just as important to a TimeSpender as

knowing when the next soccer game starts. Events are events, may they take

an hour or 10 years.

The SkiCal strategy does not change the prerequisites for building a good directory as itemized above. On the contrary unless these criteria can be satisfied one can not consider the approach successful. So we will address the items again one by one, briefly in this new context.

Commonality in attributes - From the TimeSpender POV, this has not caused problems for the current major users of SkiCal - the tourism sector, but as multi-domain coverage increases, we might end up creating multi-level decision trees similar to those of Yahoo or the Open Directory Project . For each branch of such a tree we run the risk of users timing out. Hopefully natural language searches can alleviate some of this dilemma. Initiatives such as Biztalk and UDDI borrow classification systems from the statistics community, such as SIC and NAICS. SkiCal has favoured International ISIC rev 3 and CPC codes administrated by the United Nations, but all of these codes are heavily generalized making them inadequate for detailed classification.

Precision versus effectiveness - Time and place precision sic. WHEN and WHERE, is high in SkiCal publishing, without decreasing effectiveness, but the other Wha's are subject to fuzzier categorization. The proposed remedy is to establish online public libraries of domain specific taxonomies that can be shared both by publishers and search engines, but these libraries are not yet in place, and since resource ontologies are often dynamic, these repositories bring on versioning and time axis problems of their own.

Media choice - So far, most of SkiCal publishing is pure Internet, but a significant proportion is filtered into Quark or PDF type representations for use in newspaper listings and flyers. The largest newspaper in Sweden, Aftonbladet, arranges their event calendar in this manner. The SkiCal consortium sees no size related problems for SkiCal.

Timeliness - When resource providers are responsible for publishing and updating their own content, there is an incentive for keeping information up-to-date, but there are problems as long as publishers do not see the SkiCal as their primary publishing channel.

Utility aspects - Here again it is the TimeSpender POV that glues together SkiCal information. This is a service for people making decisions as to how to spend their time and therefore utility commonality is high.

Completeness - In 2002, a government directive will radically increase SkiCal funding and consequently increase completeness, but there is still a long haul before one can begin to claim completeness.

Quality - Currently SkiCal content quality is quite high, since much of it is monitored by municipal information offices and newspapers, but as usage increases quality will increasingly become an issue to be dealt with.

Of course the SkiCal working group had no idea of what UDDI was or would be. The feasibility of building one or two large directories to facilitate the entirety of SkiCal resources was ruled out as being monopolistic, anti-competitive and certainly unrealistic. The group reasoned (seemingly incorrectly) that XML would inevitably replace HTML as the language of choice on the Internet and that all SkiCal providers could publish event and resource objects in the form of XML web pages. This would mean very little disruption of what providers were already doing. With the help of XSLT they could even retain their original database schema if desired.

Once all SkiCal information existed on the net in XML, it would be the

work of search engines to index it. Portals would either be replaced by

Search Engines or distinguish themselves by acting as intelligent infomediaries.

It was never thought, no matter how well structured the SkiCal corpus might

be, that infomediaries would become redundant. On the contrary it was observed

that once infomediaries were relieved of the burden of acquiring content,

they might have a much easier time turning a profit. . Adequate uniqueness

in resource description could be maintained if all resources utilized correct

temporal-spatial coordinates and simultaneously the correct dating of resources

would save TimeSpenders the nuisance of wading through tombstones of expired

events and out-of-date time schedules.

SkiCal is more about the use of unified schemas than building directories, and the apparent failure of XML to conquer the web, though discouraging, is certainly not a disaster for the SkiCal effort. The working group is eagerly following the Web services initiative and rethinking SkiCal to fit into this paradigm. As for the business model, it is obvious that SkiCal is the work of Bob. Without Bob's intervention, there would be no SkiCal today. But within the framework SkiCal is creating, there is room for almost any of the business model combinations indicated above. That is an essential part of the strategy.

An up-to-date report on the current state of SkiCal will be given at the

conference.

Proximities : Traditionally one would also speak of specificities - based on likeness of method, form or goal. We combine both terms here for the sake of simplicity.

Orderly Information Environments:

The use of the word orderly in this designation might be considered

superfluous since by many definitions information is order.

UDDI: But the group did look at a running a registry that included all sites offering SkiCal compliant listings and this is closer to the UDDI .approach